Art

City

Catalog view is the alternative 2D representation of our 3D virtual art space. This page is friendly to assistive technologies and does not include decorative elements used in the 3D gallery.

METEMPSYCHOSIS 2.0: DECOMPOSERS

Spaces in this world:

Statement:

METEMPSYCHOSIS 2.0: DECOMPOSERS

This section of the exhibition honors the quiet power of decomposition as a creative force.

Decomposers are the unseen workers of the earth — fungi, bacteria, and other organisms that dismantle matter, return it to the soil, and make life possible again. In their work we find a radical model of intelligence: collaborative, non-linear, and unceasingly generous.

In a culture obsessed with permanence, status, and accumulation, decomposition offers a different wisdom — that endings are beginnings, that rot nourishes, that collapse is not failure but transformation. Here, the gallery becomes a living ground of fungi, slimes, and other invisible recyclers, whose hidden networks remind us of our entanglement with all life.

Artists in this section engage decomposition as both material and metaphor. Their works reveal decay not as destruction, but as an act of care and renewal — an intelligence that dismantles the waste of human privilege and excess, and transforms it into fertile possibility.

To celebrate the decomposers is to recognize the cycles that sustain us, and to acknowledge the fragile ecologies that labor tirelessly, beyond human visibility, to resist ecocide and regenerate the world.

Curated by Xristina Sarli

Work by Helena Elston, Mizuki Ishikawa, Sharlene Durfey, Xristina Sarli

3D Environment Description:

Here we explore the vital work of fungi, bacteria, and earthworms—nature’s original recyclers. These organisms break down dead matter and return it to the ecosystem as life. Through artistic and scientific interpretations, this area celebrates the quiet power of decomposition as a creative force.

When you have an empty bottle, do you recycle it so the plastic or glass can be used again? Nature has its own recycling system: a group of organisms called decomposers.

Decomposers feed on dead things: dead plant materials such as leaf litter and wood, animal carcasses, and feces. They perform a valuable service as Earth’s cleanup crew. Without decomposers, dead leaves, dead insects, and dead animals would pile up everywhere. Imagine what the world would look like!

More importantly, decomposers make vital nutrients available to an ecosystem’s primary producers—usually plants and algae. Decomposers break apart complex organic materials into more elementary substances: water and carbon dioxide, plus simple compounds containing nitrogen, phosphorus, and calcium. All of these components are substances that plants need to grow.

Some decomposers are specialized and break down only a certain kind of dead organism. Others are generalists that feed on lots of different materials. Thanks to decomposers, nutrients get added back to the soil or water, so the producers can use them to grow and reproduce.

Most decomposers are microscopic organisms, including protozoa and bacteria. Other decomposers are big enough to see without a microscope. They include fungi along with invertebrate organisms sometimes called detritivores, which include earthworms, termites, and millipedes.

Fungi are important decomposers, especially in forests. Some kinds of fungi, such as mushrooms, look like plants. But fungi do not contain chlorophyll, the pigment that green plants use to make their own food with the energy of sunlight. Instead, fungi get all their nutrients from dead materials that they break down with special enzymes.

The next time you see a forest floor carpeted with dead leaves or a dead bird lying under a bush, take a moment to appreciate decomposers for the way they keep nutrients flowing through an ecosystem.

Author

National Geographic Society

Artworks in this space:

Turkey Tail Disco

3D scan of wooden sculpture, 2024 Turkey Tail Disco is a wooden sculpture created to reimagine the playful spirit of my mushroom-inspired paper masks through a new material language. By translating the lightweight, ephemeral qualities of paper into natural wood fibers, the work elevates the technique while maintaining the whimsy and organic vitality that define my work. Playing with scale, I’ve enlarged forms like turkey tails and lemon discos—fungi that are typically delicate and minute—into monumental presences. This shift invites viewers to reconsider the unnoticed beauty of small natural phenomena and to experience them with renewed wonder. Sharlene Durfey François, Shhhrooms

The Decomposed Mycelial Dress

This dress was designed to decompose. Made from polyester and cotton textile waste bound with mycelium, it explores transformation, decay, and renewal, revealing fashion as a living system rather than a static object. Though no longer growing, the piece captures a moment in the material’s life cycle, inviting reflection on impermanence and the potential for regeneration within what we discard.

The Decomposed Mycelial Dress

This dress was designed to decompose. Made from polyester and cotton textile waste bound with mycelium, it explores transformation, decay, and renewal, revealing fashion as a living system rather than a static object. Though no longer growing, the piece captures a moment in the material’s life cycle, inviting reflection on impermanence and the potential for regeneration within what we discard.

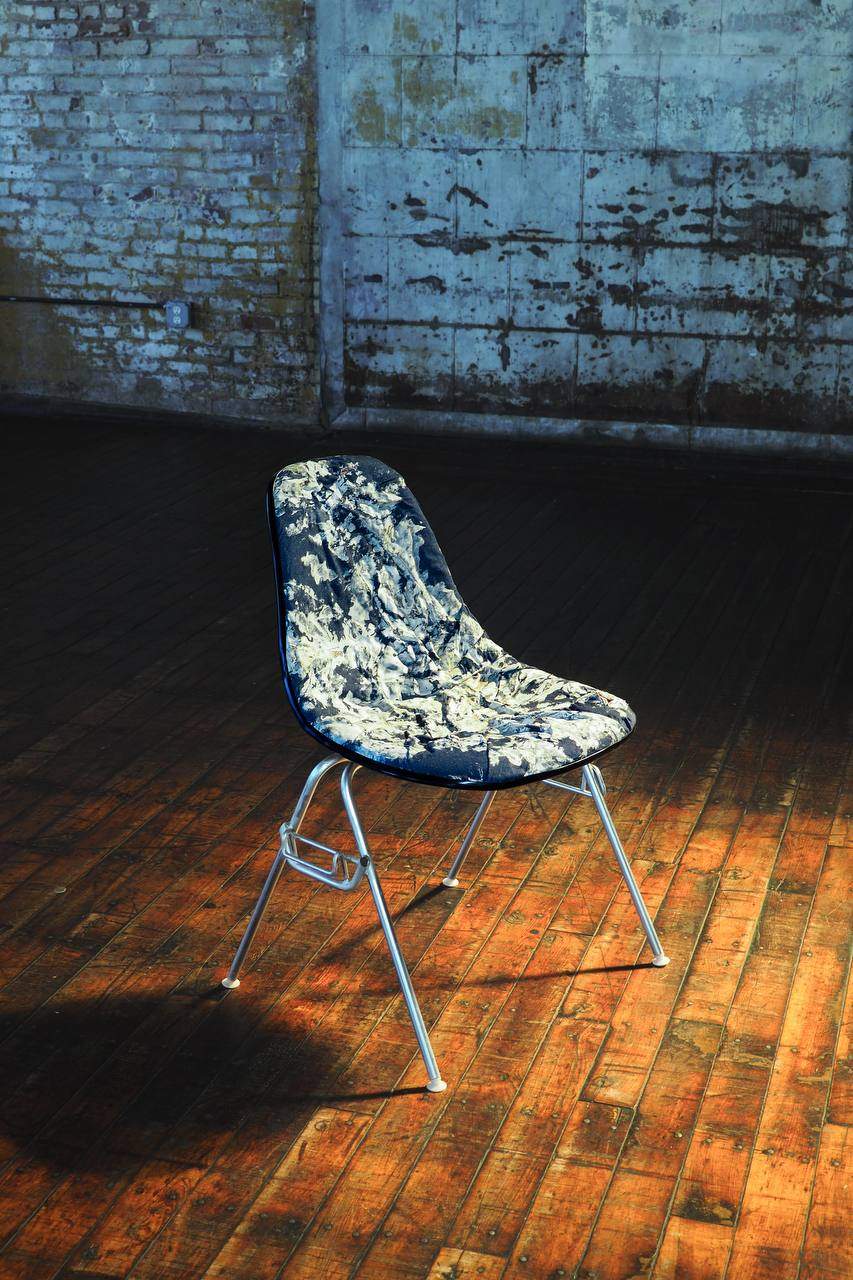

Inoculation Chair

This work reimagines domestic comfort through regenerative material design. Made from mycelium-bound denim and polyester textile waste, the piece reupholsters a classic Eames molded fiberglass chair once covered in a destroyed Alexander Girard fabric. By layering new life onto a mid-century icon, the chair explores how sustainable materials can inhabit our everyday environments, offering a vision of renewal that is both tactile and functional.

Inoculation Chair

This work reimagines domestic comfort through regenerative material design. Made from mycelium-bound denim and polyester textile waste, the piece reupholsters a classic Eames molded fiberglass chair once covered in a destroyed Alexander Girard fabric. By layering new life onto a mid-century icon, the chair explores how sustainable materials can inhabit our everyday environments, offering a vision of renewal that is both tactile and functional.

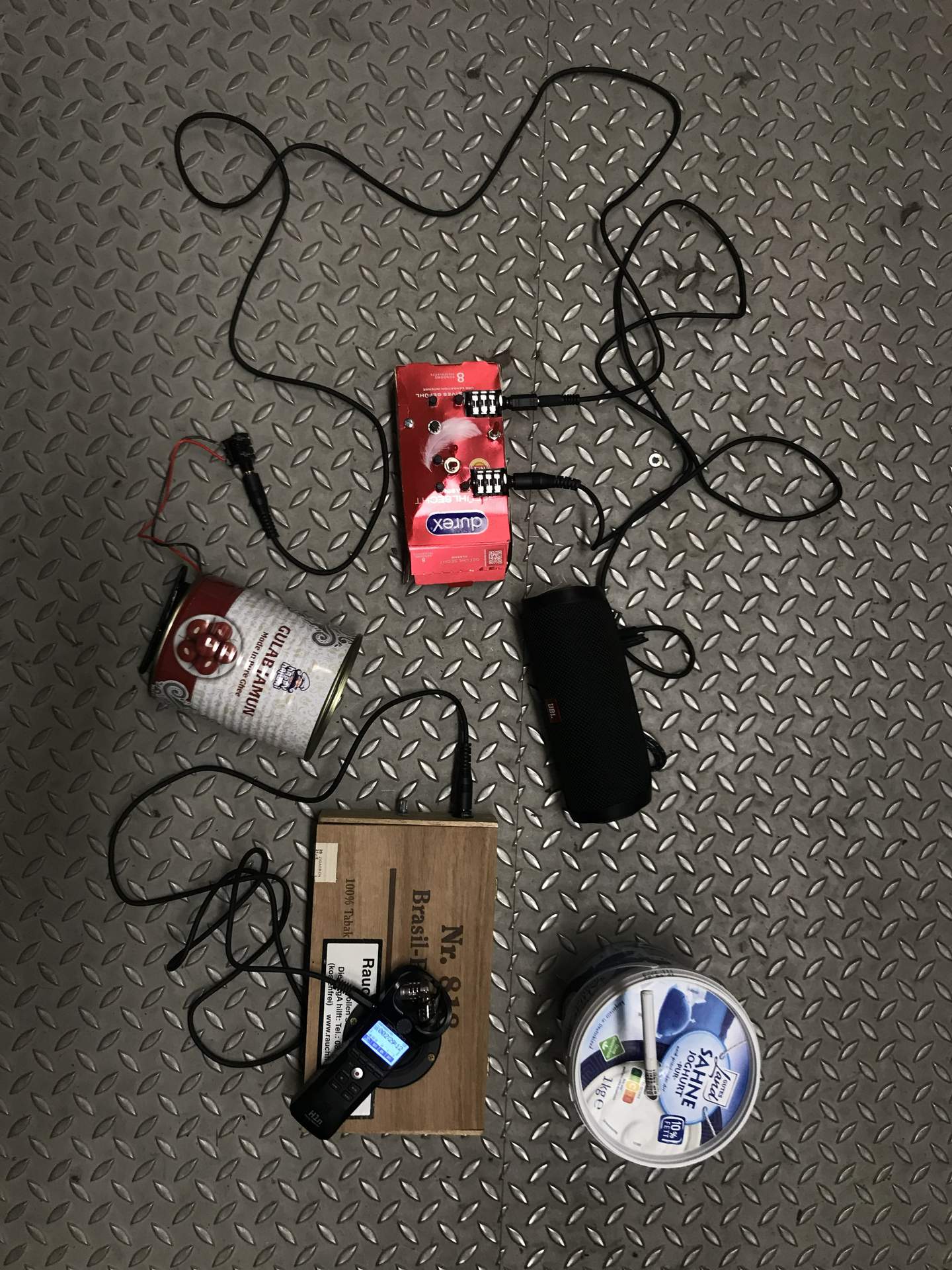

Instruments of Sonic Decay

3D Scan: “Instruments of Sonic Decay” This 3D scan captures Mizuki’s assemblage of handmade instruments—objects once discarded, now reanimated. Composed of found materials and refuse, these hybrid devices exist between sculpture and sound machine. Each dent, rusted edge, and improvised wire becomes a trace of transformation, where decay is not an end but a process of re-tuning the everyday. The scan freezes a moment in this fragile ecology of sound and matter—a still life of repurposed noise. Mizuki Ishikawa Mizuki Ishikawa is a Berlin-based improviser and sound artist. In her improvisations with objects and DIY electronics, she shapes the acoustic environment of a space using everyday objects and feedback techniques, while exploring performance through simple gestures and ordinary activities. Her project Nandeyanen (launched in 2023) combines noise with psychedelic trance music, using improvisation to capture the moment. Built on over 10 years of experience in Ableton Live and incorporating modular synthesis, the project emphasizes low frequencies as a physical experience and layered textures to induce trance states and altered perception. Through improvisation and communal listening, Nandeyanen integrates space, audience, and time into cohesive sonic experiences.

Rituals of Repurposing

In performance, Mizuki Ishikawa breathes new life into waste. Through touch, vibration, and improvisation, refuse becomes resonance. Tin, plastic, cardboard, and circuitry merge into unpredictable rhythms—metallic, percussive, droning. Each gesture negotiates between control and chaos, crafting a ritual where creativity and entropy coexist. The act of sounding becomes an alchemy of transformation: from garbage to instrument, from daily object to a work of art. Mizuki Ishikawa Mizuki Ishikawa is a Berlin-based improviser and sound artist. In her improvisations with objects and DIY electronics, she shapes the acoustic environment of a space using everyday objects and feedback techniques, while exploring performance through simple gestures and ordinary activities. Her project Nandeyanen (launched in 2023) combines noise with psychedelic trance music, using improvisation to capture the moment. Built on over 10 years of experience in Ableton Live and incorporating modular synthesis, the project emphasizes low frequencies as a physical experience and layered textures to induce trance states and altered perception. Through improvisation and communal listening, Nandeyanen integrates space, audience, and time into cohesive sonic experiences.

Rituals of Repurposing

In performance, Mizuki Ishikawa breathes new life into waste. Through touch, vibration, and improvisation, refuse becomes resonance. Tin, plastic, cardboard, and circuitry merge into unpredictable rhythms—metallic, percussive, droning. Each gesture negotiates between control and chaos, crafting a ritual where creativity and entropy coexist. The act of sounding becomes an alchemy of transformation: from garbage to instrument, from daily object to a work of art. Mizuki Ishikawa Mizuki Ishikawa is a Berlin-based improviser and sound artist. In her improvisations with objects and DIY electronics, she shapes the acoustic environment of a space using everyday objects and feedback techniques, while exploring performance through simple gestures and ordinary activities. Her project Nandeyanen (launched in 2023) combines noise with psychedelic trance music, using improvisation to capture the moment. Built on over 10 years of experience in Ableton Live and incorporating modular synthesis, the project emphasizes low frequencies as a physical experience and layered textures to induce trance states and altered perception. Through improvisation and communal listening, Nandeyanen integrates space, audience, and time into cohesive sonic experiences.

Instruments of Sonic Decay

Mizuki’s assemblage of handmade instruments—objects once discarded, now reanimated. Composed of found materials and refuse, these hybrid devices exist between sculpture and sound machine. Each dent, rusted edge, and improvised wire becomes a trace of transformation, where decay is not an end but a process of re-tuning the everyday. The scan freezes a moment in this fragile ecology of sound and matter—a still life of repurposed noise. Mizuki Ishikawa Mizuki Ishikawa is a Berlin-based improviser and sound artist. In her improvisations with objects and DIY electronics, she shapes the acoustic environment of a space using everyday objects and feedback techniques, while exploring performance through simple gestures and ordinary activities. Her project Nandeyanen (launched in 2023) combines noise with psychedelic trance music, using improvisation to capture the moment. Built on over 10 years of experience in Ableton Live and incorporating modular synthesis, the project emphasizes low frequencies as a physical experience and layered textures to induce trance states and altered perception. Through improvisation and communal listening, Nandeyanen integrates space, audience, and time into cohesive sonic experiences.

0100010010101001010001001

Like mushrooms, mold is a type of fungus. Fungus is a kind of living organism that produces spores and feeds on organic matter such as rotting food. There are many different kinds of mold that grow in different places. Some molds only grow on wood, others tend to be found on decaying plant or animal matter, and some are most commonly found on food. Several different kinds of mold appear on bread, so they are referred to as bread molds. Although they are different species, all of these molds have a few things in common. Like all molds, bread molds reproduce by creating spores. Spores are tiny, often microscopic, particles from which fully formed molds eventually grow. Mold spores are present almost anywhere you find moisture and organic matter. They can drift through the air or land in water or food, meaning that they are almost always present in the wild and indoors. Fortunately, the vast majority of mold spores are harmless. Bread molds thrive on bread because of the rich organic materials found in it. Sugar and carbohydrates fuel the growth of mold spores. This is why bread left out in the open begins to grow visible mold in only five to seven days. The specific species of bread mold depends on the type of spores that are present in the environment.

Profundō, ergō rēgnō (I waste/squander, therefore I reign.)

1. Conspicuous Consumption and the Origins of “Waste as Power” Thorstein Veblen’s Concept -Conspicuous Consumption. Sociologist Thorstein Veblen coined this term to describe the way elites purchase or use goods not just for utility or enjoyment but primarily to display wealth or status. -Conspicuous Waste. Part of that display often involves waste or destruction—demonstrating that the elite can afford to forgo practical reuse. -Ancient and Medieval Elites Roman Feasts. Elite Romans hosted spectacular banquets (e.g., as described in the Satyricon by Petronius). These feasts were infamous for their abundance of food and exotic dishes, much of which was left uneaten or casually thrown away to convey extravagance. -Medieval Courts in Europe. Kings and nobles organized feasts where the quantity of food (and subsequent waste) was meant to impress guests. Leftovers were sometimes distributed among servants or donated as alms for the poor, but large portions were simply discarded. 2. Ritual Destruction as Display of Power -Potlatch Ceremonies (Pacific Northwest) Gift-Giving and Waste. Among some Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest (e.g., the Kwakwakaʼwakw, Tlingit, and Haida), potlatches involved giving away or even intentionally destroying valuable goods—blankets, copper shields, canoes—to showcase wealth and status. -Social and Spiritual Motives. This ritual burning or destruction wasn’t random but served to elevate the host’s prestige, underline social ranks, and reinforce community ties. Funerary and Sacrificial Rites -Egyptian Pharaohs. In ancient Egypt, burying massive amounts of grave goods (including jewelry, tools, and sometimes even animals or servants in earlier periods) was a statement of power and divine kingship. These items were effectively “removed” from circulation, a form of waste from a purely economic standpoint. -Chinese Imperial Tombs. Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Terracotta Army is a prime example of vast resources devoted to a tomb—thousands of life-sized figures, chariots, and weapons that were never to be used by the living again. 3. Sharing, Trading, and Partial Reuse While much was wasted, some elite surplus did find other pathways: -Alms and Charity. Especially in medieval Christian Europe and in Islamic societies, distributing leftover food and goods could be an act of charity that also enhanced the giver’s reputation for piety or generosity. In many royal courts, feeding the poor (or at least a portion of them) during festivals or public ceremonies was a political move to keep favor with the populace. -Spoils and Retainers. Leftover banquets or surplus goods would frequently be distributed among a lord’s household staff, guards, or supporters. These distributions could help maintain loyalty. -Recycling of Materials. Although “upcycling” is a modern term, historically there were forms of reuse (like melting down precious metals or reusing fabric in new garments). However, these were often motivated by immediate economic or practical needs rather than environmental considerations. 4. The Political Dimension of Waste -Demonstrating Control Over Resources Bread and Circuses (Panem et Circenses). In ancient Rome, providing free grain or staging lavish games was a way to keep the populace content while showing off the empire’s abundance. These events generated huge waste—food, damaged amphitheaters, disposable gladiatorial equipment—but they served a political purpose: showcasing imperial munificence and power. -Sumptuary Laws Restricting Others’ Consumption. Elite waste was sometimes checked by laws designed to maintain class distinctions—for example, only certain ranks could wear specific colors or fabrics. Despite these laws, the monarch or top elites themselves often broke the norms or found loopholes to continue flaunting wealth. 5. Modern Parallels and Shifts Luxury Branding and Planned Obsolescence. Today’s fashion and electronics industries sometimes deliberately destroy unsold goods to keep prices high—an echo of “waste as a status symbol.” -Philanthropy vs. Waste. Modern billionaires engage in notable philanthropy, but they also maintain lifestyles that consume large amounts of resources (private jets, mega-yachts). This can generate immense waste without always being recycled or repurposed. Environmental Awareness and “Upcycling.” Contemporary discussions of sustainability and waste reduction are relatively new. Historical elites rarely worried about the environmental impact of their extravagances. Today, some high-profile individuals adopt “green” reputations or emphasize charitable giving to offset the negative optics of conspicuous waste. The cycle of hoarding, display, and eventual disposal underlines a universal theme: when one has the resources to afford “waste,” it sends a potent message of status and power to onlookers and rivals alike. Food Waste Activism Farmers in many regions of the world have used the destruction or dumping of their produce as a powerful statement of protest: to draw attention to unsustainable market prices, corporate control and other disturbing insights of the Global Food System policies. Destroying or dumping agricultural products is a very graphic, attention-grabbing demonstration. It highlights the discrepancy between abundance on one hand, and poverty or unsustainable pricing on the other. Many of these protests are aimed at prompting government intervention—such as subsidies, price supports, or protectionist measures—or at drawing the public’s attention to unfair trade practices by multinational companies. https://www.euronews.com/green/2024/03/29/in-pictures-farmers-spray-manure-and-throw-beets-to-protest-eu-agricultural-policy https://www.france24.com/en/france/20241119-french-farmers-protests-eu-trade-deal-south-america-mercosur-bloc https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_farmers%27_protests Fashion activism (Status and Waste) “Fast-Fashion Waste” often conjures images of wastelands ripped from a dystopian nightmare. In places like the Atacama Desert in Chile or landfills in Ghana, towering heaps of unsold and returned clothing—shipped from Europe, Asia, and North America—vividly illustrate the environmental toll of a consumption cycle that discards garments at an alarming rate. These massive textile dumps not only scar the landscape; they also reveal a deeper crisis of unsustainable production, irresponsible disposal, and global inequities in how waste is managed. https://www.bbc.com/bbcthree/article/5a1a43b5-cbae-4a42-8271-48f53b63bd07 https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2021/11/8/chiles-desert-dumping-ground-for-fast-fashion-leftovers https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/aug/16/textile-waste-landfill-creatives-transform-rags-to-riches-upcycling-ghana-chile-pakistan https://youtu.be/rKLCd7c-C2Q?si=9XCHCEXbI5lyq8BA E-waste activism https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/electronic-waste-(e-waste)

Fresh Fruit Watermelon Jelly

Compost

Compost is a mixture of ingredients used as plant fertilizer and to improve soil's physical, chemical, and biological properties. It is commonly prepared by decomposing plant and food waste, recycling organic materials, and manure. The resulting mixture is rich in plant nutrients and beneficial organisms, such as bacteria, protozoa, nematodes, and fungi. Compost improves soil fertility in gardens, landscaping, horticulture, urban agriculture, and organic farming, reducing dependency on commercial chemical fertilizers. The benefits of compost include providing nutrients to crops as fertilizer, acting as a soil conditioner, increasing the humus or humic acid contents of the soil, and introducing beneficial microbes that help to suppress pathogens in the soil and reduce soil-borne diseases. At the simplest level, composting requires gathering a mix of green waste (nitrogen-rich materials such as leaves, grass, and food scraps) and brown waste (woody materials rich in carbon, such as stalks, paper, and wood chips). The materials break down into humus in a process taking months. Composting can be a multistep, closely monitored process with measured inputs of water, air, and carbon- and nitrogen-rich materials. The decomposition process is aided by shredding the plant matter, adding water, and ensuring proper aeration by regularly turning the mixture in a process using open piles or windrows. Fungi, earthworms, and other detritivores further break up the organic material. Aerobic bacteria and fungi manage the chemical process by converting the inputs into heat, carbon dioxide, and ammonium ions.

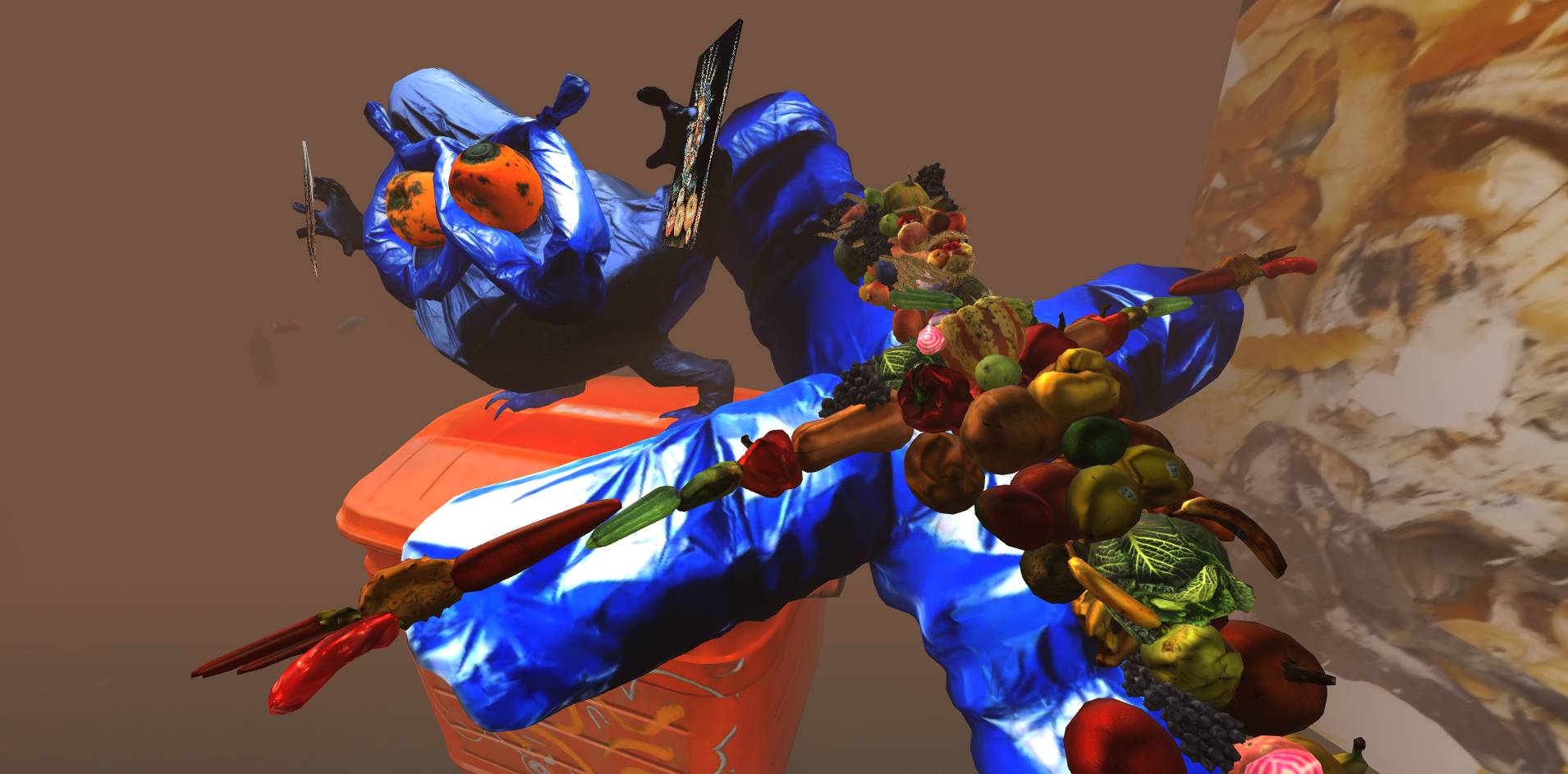

Vertumnus Compositum

The 3D model of Vertumnus Compositum is inspired Vertumnus is an oil painting produced by the Italian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo in 1591 that consists of multiple fruits, vegetables and flowers that come together to create a portrait of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. In Roman mythology, Vertumnus is the god of changing seasons, gardens, fruit trees, and plant growth. The portrait of the emperor is created out of plants, flowers and fruits from all seasons: gourds, pears, apples, cherries, grapes, wheat, artichokes, beans, peas, corns, onions, cabbage foils, chestnuts, figs, mulberries, plums, pomegranates, various pumpkins and olives. Arcimboldo's choice of fruits, vegetables and flowers not only alluded to Emperor Rudolf II's reign, but also referenced his power and wealth. During the Renaissance, collections of oddities and foreign luxury goods were status symbols for the rich. Great families of the Renaissance such as the Medici collected flora, foods, animals (both living and dead) and other materialistic objects to display their wealth and reach (as many people in those days could not afford such luxuries) and thus, goods from the New World began to trickle into the kunstkammer or wunderkammer of many elites.Arcimboldo's use of corn as Emperor Rudolf II's ear (a crop originating from the New World) thus can be seen as a pointedly political decision. By putting in these particular foreign crops, Rudolf II is revealing that he has access to these items showcasing his power and wealth. See more in WIKI link below. Historically, lavish consumption and the production of waste have been key markers of power and status. Whether it was Roman nobility discarding banquet leftovers, pharaohs burying treasure in tombs, or Northwest Coast peoples burning valuables in a potlatch, waste itself—sometimes ritualized, sometimes accidental—was a direct or indirect sign of dominion over resources. Sharing with the poor or reusing materials occurred in some contexts, but the main aim was to communicate abundance and superiority, not to recycle in the modern sense. The cycle of hoarding, display, and eventual disposal underlines a universal theme: when one has the resources to afford “waste,” it sends a potent message of status and power to onlookers and rivals alike.

Good Soil!

Remix with 1:54 Blue Jello YouTube clip, www.youtube.com/@wormlapse

Regenerative Fashion

Imagine disposing of an old jacket by simply composting it. In Regenerative Fashion, a decomposing denim garment merges with mycelial growth, symbolizing fungi’s role as “professional decayers” in nature. Through a 3D depiction of fungi colonizing textile waste, the piece envisions a future where clothing can naturally break down and return nutrients to the environment rather than lingering in landfills. This artwork underscores the potential of mycoremediation—the process by which fungi degrade or neutralize pollutants—and challenges fast-fashion norms by illustrating how design and ecology can work in tandem to create truly circular, zero-waste systems. Fun Fact Certain fungal species can break down synthetic dyes and other chemical residues in textiles, highlighting their potential as powerful allies in mitigating environmental pollution.

Jack Frost

The strain "Jack Frost" of Psilocybe cubensis is a relatively new addition to the catalog of psilocybin mushrooms. It is a hybrid strain that was created by crossing two well-known strains: True Albino Teacher (TAT) and Albino Penis Envy (APE). These two parent strains are notable for their unique genetic mutations that result in remarkable fruiting bodies characterized by a ghostly white appearance. The hybridization process aims to combine desirable traits from both parent strains. TAT contributes its robustness and relatively high yield while maintaining the potent psychoactive effects. APE, on the other hand, is renowned for its exceptionally high potency. The result is a strain that is not only visually striking but also potent in its psychoactive effects. Jack Frost has gained popularity within the mycology community for its distinct appearance, featuring caps and stems that are often almost entirely white, and for packing a strong psychoactive punch, making it a sought-after strain for both cultivators and psychonauts alike.

बहुचरा माता, Bahuchara Mata

fungi (trichoderma and panelus stipticus) on wooden murti, 2025 This sculpture was found discarded — painted, decorated with fur, and thrown away. When I discovered its wooden core, I began to restore not the paint, but its natural form — to let something else grow. Part of my Belluminescent series, God lives just below the surface of the soil, this work brings together religious symbolism, fungal science, and queer embodiment. I grow bioluminescent fungi like Panellus stipticus, which glow briefly in darkness — powered by the compound luciferin, whose name means “light-bringer” yet is bound to the myth of Lucifer, the fallen. This ambiguity opens space for challenging narratives that cast the non-human — or the non-conforming — as antagonist. The sculpture became colonized not only by Panellus, but also by Trichoderma, a second fungal species often dismissed as contamination. Yet Trichoderma is widely used to regenerate soil, fight plant disease, and stimulate growth. In the fungal world, binaries like good and evil fall apart. One being’s invader is another’s protector. One god glows. The other digests. Possibly a depiction of Bahuchara Mata, a goddess sacred to trans and non-binary communities in India, this murti is now inhabited by multiple living systems — a polyphony of survival, conflict, and co-existence. This is not a failed experiment. It is a more complete one. A glow with no flame, a god with no face. Would you still bow?

BALANCE IS FOR GODS

*Cosmic Perspective 1.Who can judge the future? From a cosmic perspective, the future is vast, indifferent, and shaped by universal forces. Stars will die; galaxies will collide. Judgment is irrelevant on this scale. 2.Who can judge the past? The past is written in stardust, in the cosmic microwave background, in the light of distant stars. It is observed but not judged. 3.Whose knowledge matters? Cosmic knowledge humbles us, reminding humans of their smallness and the importance of fostering life on this fragile planet. **Geological Perspective (Rocks, Mountains, Earth’s Crust) 1.Who can judge the future? Geological timeframes dwarf human concerns. From this perspective, the future unfolds in millions of years. Mountains erode; tectonic plates shift. The focus is on inevitability rather than judgment. 2. Who can judge the past? Rocks hold the record of Earth’s history—volcanic eruptions, sedimentary layers, fossilized life. They silently testify to what has been without moral judgment. 3. Whose knowledge matters? Geological knowledge matters because it reveals the long-term impacts of processes like erosion, fossilization, and climate shifts, helping us understand deep time. ***Ecosystem or Gaia Perspective 1.Who can judge the future? From a planetary or ecosystem perspective, the future is not about judgment but about maintaining balance. Feedback loops—like climate regulation or biodiversity thresholds—are the metrics by which the future is assessed. 2.Who can judge the past? Ecosystems judge the past by the stability they inherit. Extinctions, pollution, and habitat loss echo as disruptions that shape resilience or fragility. 3.Whose knowledge matters? The ecosystem perspective values collective knowledge. The interplay of all species and processes contributes to the health of the whole. ****Rivers, Oceans, or Watersheds’ Perspectives 1.Who can judge the future? For rivers and oceans, the future is about flow and continuity. Dams, pollution, and climate change are disruptions to this natural flow, and they judge the future by whether it allows life to thrive. 2.Who can judge the past? Rivers carve the past into landscapes, and oceans hold records of Earth's climate history in their depths. These perspectives “judge” based on the patterns left behind—eroded shorelines or coral reef bleaching. 3.Whose knowledge matters? Hydrological cycles teach us the value of interconnected systems. The knowledge of water—its movement, storage, and transformation—matters for all life. *****Microbial Perspectives: 1. Who can judge the future? Microbes, as the foundation of life, may see the future as a web of potentialities. Their role in cycles like nitrogen fixation and digestion suggests that the future is built one interaction at a time. 2. Who can judge the past? For microbes, the past might be stored in genetic material—an evolutionary record of survival strategies. They show that the past matters insofar as it provides solutions to current and future challenges. 3. Whose knowledge matters? Microbial knowledge is unseen but essential. It reminds us that the smallest contributors to ecosystems often have the most profound impact. ******Plants’ Perspectives 1.Who can judge the future? Plants might view the future through growth and reproduction cycles, judging it by the availability of sunlight, water, and nutrients. For them, future viability depends on ecological balance and the continuity of conditions. 2.Who can judge the past? The past is etched into growth rings, soil conditions, and genetic diversity. Plants could “judge” the past based on how well ecosystems have nurtured biodiversity and resilience. 3.Whose knowledge matters? Plants exemplify the importance of slow, incremental knowledge—adapting over millennia. They remind us that patient, long-term thinking can sustain life. *******Fungi's Perspective: 1.Who can judge the future? Fungi would likely view the future as a networked, interconnected possibility rather than something to be judged. Their mycelial networks function by adapting to environmental signals, emphasizing collaboration and mutualism over judgment. 2.Who can judge the past? For fungi, the past is embedded in the soil, the decaying organic matter they recycle. Instead of judgment, fungi interpret the past through decomposition and transformation, turning history into nourishment for future growth. 3.Whose knowledge matters? Fungi might argue that all knowledge matters, especially the knowledge that arises from symbiotic relationships. They demonstrate that knowledge is distributed across networks, not centralized in any single organism or species. ********Animals' Perspectives 1.Who can judge the future? Animals often operate in cycles and rhythms tied to their immediate environments. They might view the future not as an abstraction but as a continuation of lived experience—inseparable from their habitat’s health and stability. 2. Who can judge the past? From animals’ perspectives, the past is written into instinct and memory. They embody past lessons through evolved behaviors and survival strategies, emphasizing adaptation rather than judgment. 3. Whose knowledge matters? Animal knowledge is diverse and often context-specific. Migration paths, predator-prey dynamics, or social hierarchies demonstrate that localized, embodied, and intergenerational knowledge is invaluable. *********Indigenous or Ancestral Perspectives: 1.Who can judge the future? Indigenous knowledge systems often view the future as a continuation of ancestral responsibilities. The future is judged by how well it honors past teachings and ensures the well-being of generations yet to come. 2. Who can judge the past? The past is sacred, a source of wisdom and guidance. Mistakes are not to be judged harshly but to be learned from, ensuring balance and harmony are restored. 3. Whose knowledge matters? Indigenous perspectives emphasize relational knowledge—between people, land, and non-human beings. All knowledge is interdependent and holds value in sustaining life. **********AI or Technological Perspectives 1. Who can judge the future? AI might judge the future based on data and optimization. It would focus on predictive models and maximizing outcomes rather than emotional or moral judgment. 2. Who can judge the past? The past is a dataset to analyze. Patterns, errors, and trends are examined for insights into improving future decisions. 3. Whose knowledge matters? From a technological perspective, data-driven knowledge matters most—but this raises ethical questions about who controls the data and whose narratives are included. Additional Questions Humans Could Reflect On: 1. What does it mean to belong to a system greater than ourselves? Inspired by rivers, mountains, and stars, this question emphasizes humility and interconnectedness. 2.How can we integrate different temporalities (short-term vs. long-term thinking)? Fungi, mountains, and the cosmos challenge humans to think beyond immediate concerns. 3. What role does reciprocity play in knowledge and judgment? Indigenous systems and bees teach the importance of mutual benefit and balance. 4. How can we honor the unseen forces that sustain us? Microbes, fungi, and the microbiome reveal the invisible yet essential processes humans often overlook. 5. What is the cost of prioritizing human judgment over other forms of wisdom? Technology and ecosystems remind us that human-centric thinking can lead to imbalance and degradation. NATURAL BORN WASTERS Additional Questions Humans Could Ask Inspired by Fungi: -How can we cultivate symbiotic relationships with the environment? Inspired by fungi, humans might reflect on fostering mutualism rather than exploitation in their interactions with nature. -What does it mean to decompose ethically? Drawing from fungi's role in breaking down organic material, this question invites humans to think about their legacy and ecological impact. -How can networks of connection enhance resilience? Fungal networks highlight the power of interconnection. Humans might explore how collaborative systems can address environmental and societal challenges. -What lessons can we learn from decay and regeneration? Observing how fungi transform the old into the new could prompt humans to reconsider waste, renewal, and sustainability. -What is the role of humility in hybrid ecosystems? Fungi thrive through subtle, unseen work. Humans might ask how adopting humility could improve their stewardship of the Earth. -How can we measure success beyond growth? Inspired by fungi's role in maintaining equilibrium, humans could rethink metrics of success to include balance, diversity, and sustainability. MORE MORE-THAN-HUMAN QUESTIONS: 1.How do we define justice in non-human terms? 2.What does flourishing look like for ecosystems, not just humans? 3.What would a world without humans "say" about itself? 4.How can humans make decisions that honor all life forms? 5.What does it mean to listen to the Earth’s rhythms? BALANCE IS FOR GODS 1.The first humans were created by the gods to serve them and keep the world in balance. The first humans were perfect in every way, but they were also naïve and easily led astray. The gods grew tired of their shenanigans and decided to destroy them. 2.The second humans were created from the blood of the first humans. They were stronger and wiser, but still prone to error. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 3.The third humans were created from the clay of the earth. They were the first humans to be truly mortal. The gods gave them intelligence and the ability to reason, but they were also flawed and susceptible to temptation. 4.The fourth humans were created from the fire of the sun. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for evil. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 5.The fifth humans were created from the water of the sea. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for good. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 6.The sixth humans were created from the wind. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for both good and evil. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 7.The seventh humans were created from the sperm of the first humans. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for love. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 8.The eighth humans were created from the egg of the first humans. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for life. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 9.The ninth humans were created from the dust of the earth. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for death. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 10.The tenth humans were created from the breath of the first humans. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for both life and death. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance.

The Mycomancer´s Oak

Inspired by the "Spirit in a Bottle" Tale: In this narrative, a gifted alchemist sets out on a daring journey to trap the very spirit that animates all living things—a luminous, elusive essence believed to be the quintessence of life. Armed with ancient knowledge and an unyielding ambition, he crafts a delicate glass bottle intended to serve as a vessel for this vital force. However, as the alchemist painstakingly distills natural elements and refines his process, he soon encounters an unexpected truth: the spirit is not a passive substance to be tamed and stored. It is a wild, dynamic energy that resists confinement, its essence forever in flux. The very moment it is sealed within the bottle, the spirit begins to challenge the boundaries of its transparent prison, stirring upheaval and transformation both within the vessel and in the world beyond. In the unfolding drama, the bottle comes to symbolize more than mere containment—it embodies human ambition, hubris, and the perennial struggle to impose order on the untamable forces of nature. The alchemist learns that true mastery does not lie in trapping the spirit, but rather in understanding and working with its ever-shifting nature. In letting go of the need to control, he finds a deeper harmony with the processes of transformation that govern life itself. The Message: The Greems Brothers’ “Spirit in a Bottle” is ultimately a parable about the limits of human control. It suggests that life’s most profound forces—its creativity, energy, and transformative potential—cannot be permanently confined or owned. Instead, they must be embraced in their fluidity, a reminder that our attempts to fix or capture the ever-changing spirit of existence may only lead to unintended consequences. In this way, the story invites us to recognize that true wisdom comes from working in tandem with nature’s rhythms, rather than trying to dominate them.