Art

City

Catalog view is the alternative 2D representation of our 3D virtual art space. This page is friendly to assistive technologies and does not include decorative elements used in the 3D gallery.

Prima Materia

Spaces in this world:

Links in this space:

Statement:

PRIMA MATERIA

In the time before time, when neither the stars nor the gods had names, what was there?

This world descends into primordial darkness, into the waters, slimes, and first eukaryotic forms that seeded all life. Here, non-human intelligences are encountered not only in ancient forces of matter but also in the emergent presences of artificial systems. In this alchemical chamber, slime and algorithm meet as speculative ancestors, cyborgian echoes of creation that remind us intelligence is never solely human.

The PRIMA MATERIA Pavilion becomes a site of origin stories both biological and machinic, where sacred matter, ancient gods, and synthetic minds blur into one continuum. Visitors are invited into an elemental ground zero, where myth, biology, ecology and computation intermingle to reimagine the beginnings of intelligence beyond the human.

The Pavilion unfolds across four interconnected spaces, each tracing a strand of more-than-human intelligence. Prima Materia sets the ground of origins, a place where myth and matter entwine. World Wide Waste confronts the residues of extractive culture, reimagining discarded matter as fertile ground for transformation. Decomposers highlights the quiet labor of fungi and non-human agents who recycle life back into the cycle. Finally, Mycohacking the Future envisions speculative tools and community practices that reframe biofabrication as resistance to ecocide.

Together, these spaces form a mycelial network, four chambers of one organism, inviting visitors to journey through origin, residue, decay, and future-making as inseparable movements within a living continuum.

Curated by Xristina Sarli, Berlin

Work by Alina Tofan, Alve Lagercranz, Arezou Ramezani, Emma Sicher, Enrico Dedin, Juliette Collas, Maria Dębińska, Markella Davu, Matteo Campulla, Physarum Polycephalum, Ivona Pelajic,Tanja Vujinovic, Xristina Sarli, Yiou Wang

3D Environment Description:

In the time before time, when neither the stars nor the gods had

names, what was there?

This world descends into the primordial darkness — the waters, slimes, and first eukaryotic forms that seeded all life. Here, non-human intelligences are encountered not only in the ancient forces of matter, but also in the emergent presences of artificial systems. In this alchemical chamber, slime and algorithm meet as speculative ancestors, cyborgian echoes of creation that remind us intelligence is never solely human.

PRIMA MATERIA

In the time before time, when neither the stars nor the gods had names, what was there?

This world descends into the primordial darkness — the waters, slimes, and first eukaryotic forms that seeded all life. Here, non-human intelligences are encountered not only in the ancient forces of matter, but also in the emergent presences of artificial systems. In this alchemical chamber, slime and algorithm meet as speculative ancestors, cyborgian echoes of creation that remind us intelligence is never solely human.

Prima Materia becomes a site of origin stories both biological and machinic — where sacred matter, ancient gods, and synthetic minds blur into one continuum. Visitors are invited to experience an elemental ground zero, where myth, biology, and computation intermingle to reimagine the beginnings of intelligence beyond the human.

Curated by Xristina Sarli, Berlin DE

Work by Alina Tofan, Alve Lagercranz, Arezou Ramezani, Emma Sicher, Enrico Dedin, Juliette Collas, Maria Dębińska, Markella Davu, Matteo Campulla, Physarum Polycephalum, Tanja Vujinovic, Xristina Sarli, Yiou Wang

Artworks in this space:

Secretion

Skulptur und Soundinstallation Im Rahmen von Menstrualities

Secretion

Skulptur und Soundinstallation Im Rahmen von Menstrualities

Secretion

Skulptur und Soundinstallation Im Rahmen von Menstrualities

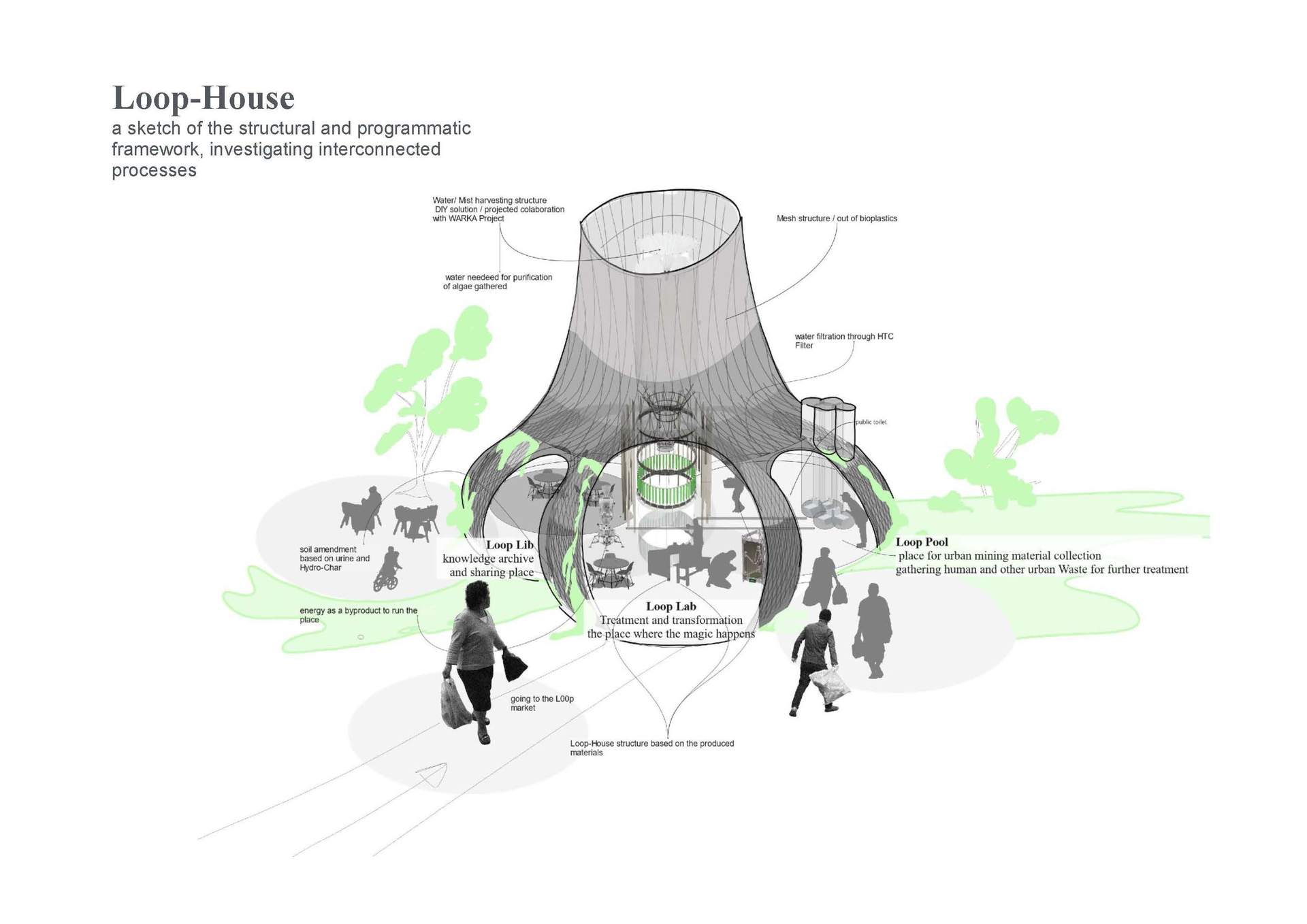

looplab

LoopLab is a collective of artists, architects, makers and researchers from various academic and civil backgrounds. Our mission is to investigate alternative sanitation systems for public spaces and break taboos around shit.

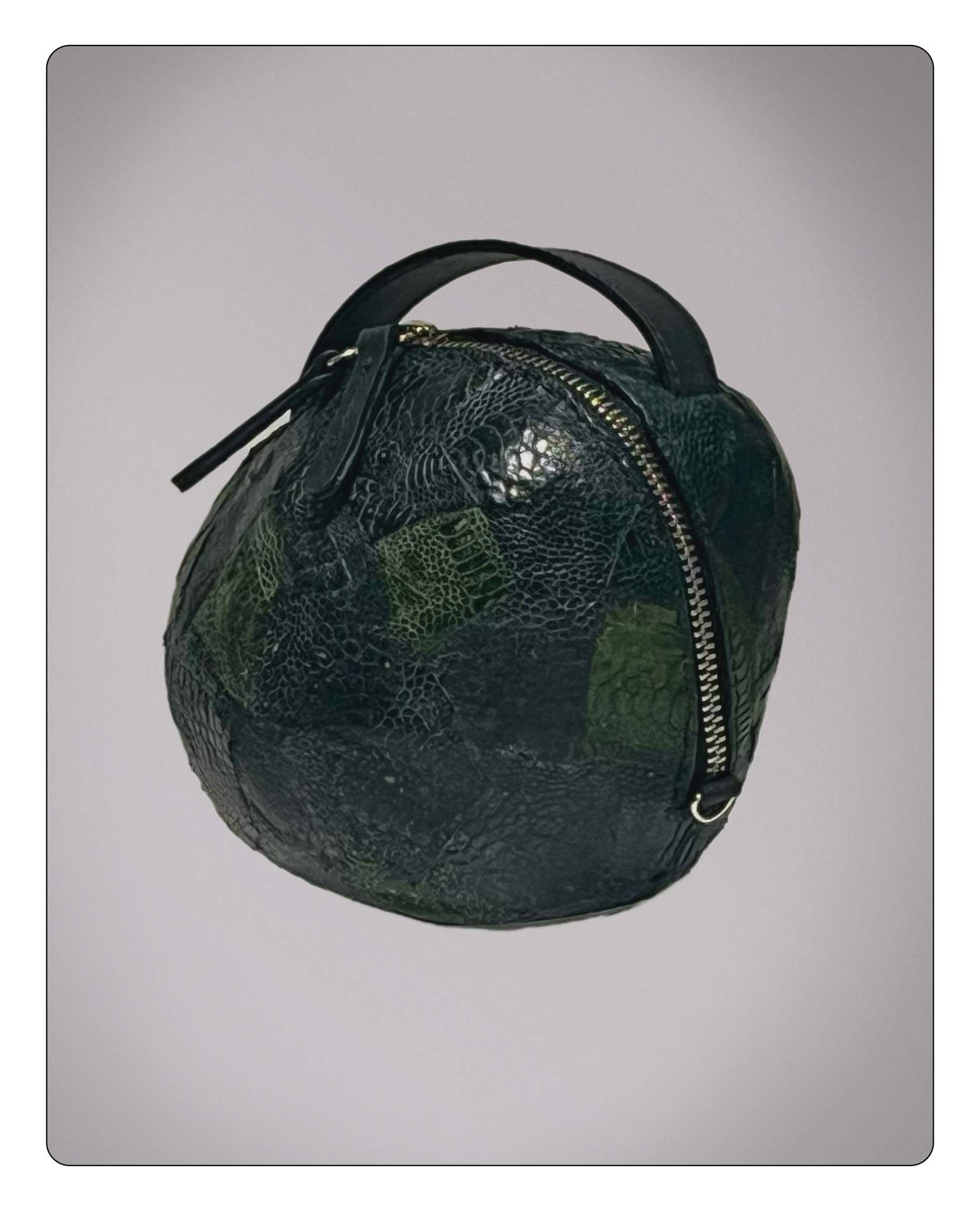

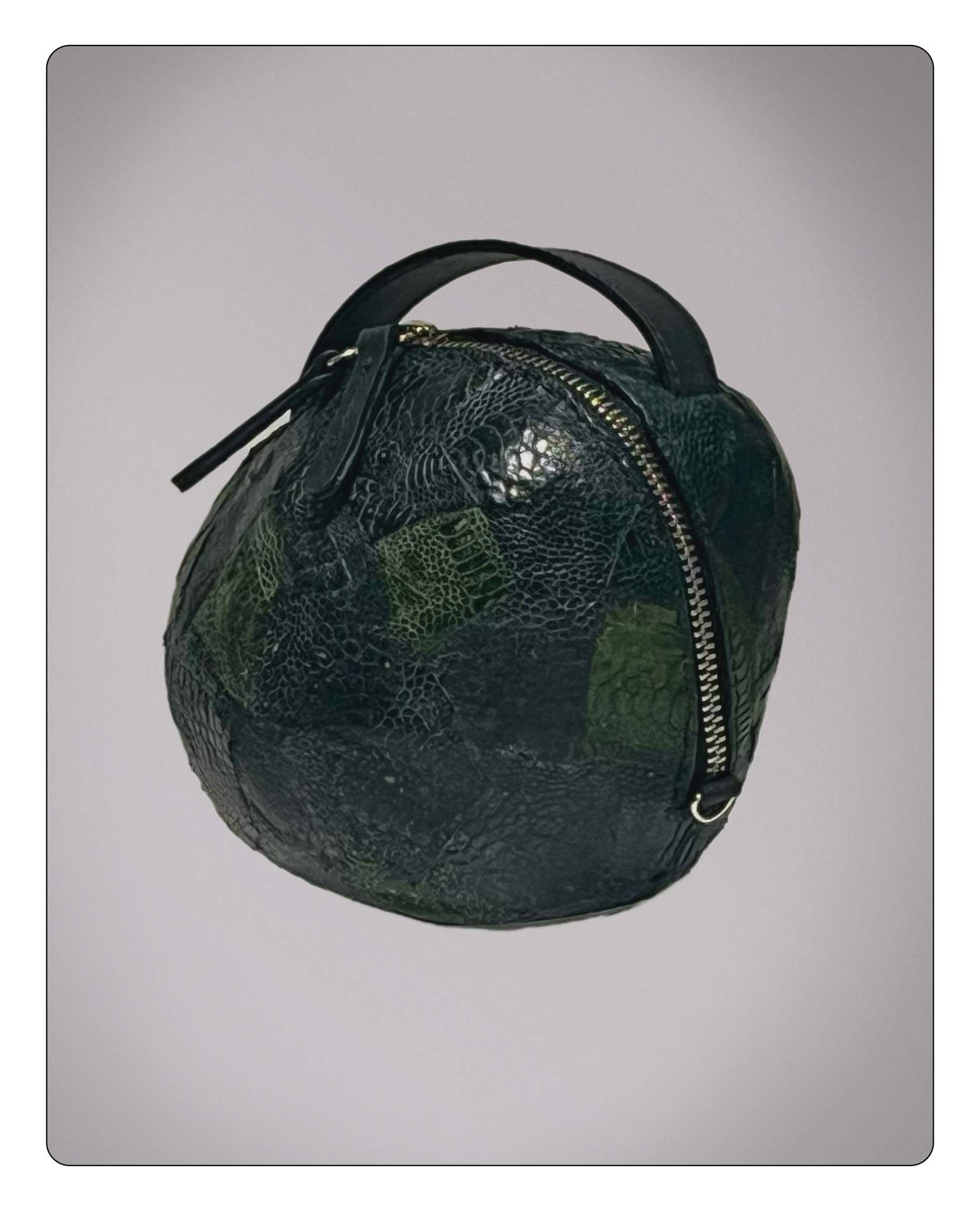

Sunglasses Case

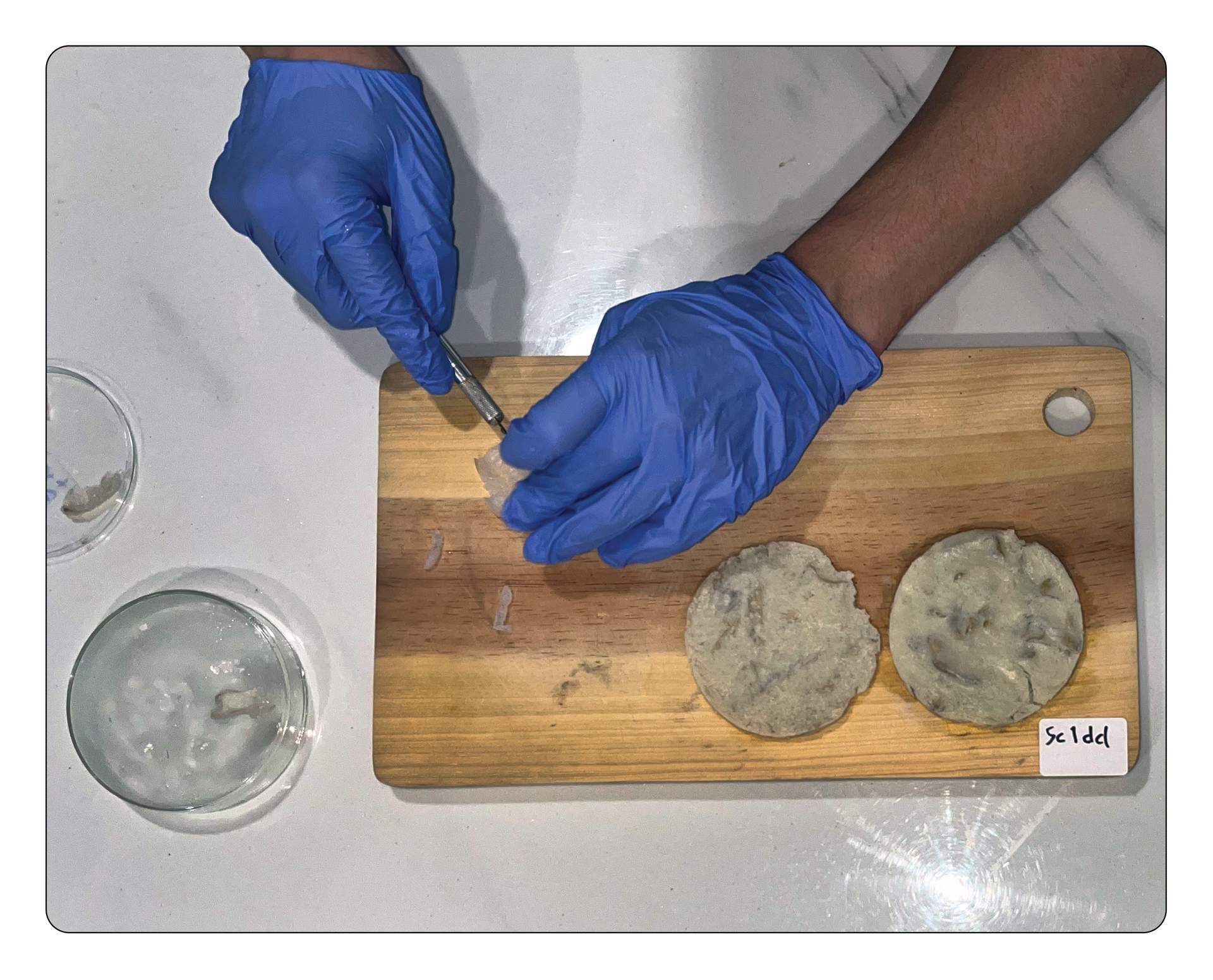

Chicken skin is the only livestock hide not commonly used for leather, primarily due to its small size. This project seeks to challenge that limitation by exploring innovative ways to create leather from chicken feet—a valuable but often overlooked waste stream in the poultry industry. By repurposing this material, we aim to reduce waste and offer a sustainable alternative. We have developed two unique techniques to fabricate chicken feet leather without the need for traditional stitching. Drawing inspiration from the papier-mâché process, we have created a method we call Cuir Mâché, allowing the small hides to be transformed into final 3D objects.

cuir mâché

Chicken skin is the only livestock hide not commonly used for leather, primarily due to its small size. This project seeks to challenge that limitation by exploring innovative ways to create leather from chicken feet—a valuable but often overlooked waste stream in the poultry industry. By repurposing this material, we aim to reduce waste and offer a sustainable alternative. We have developed two unique techniques to fabricate chicken feet leather without the need for traditional stitching. Drawing inspiration from the papier-mâché process, we have created a method we call Cuir Mâché, allowing the small hides to be transformed into final 3D objects.

cuir mâché

Chicken skin is the only livestock hide not commonly used for leather, primarily due to its small size. This project seeks to challenge that limitation by exploring innovative ways to create leather from chicken feet—a valuable but often overlooked waste stream in the poultry industry. By repurposing this material, we aim to reduce waste and offer a sustainable alternative. We have developed two unique techniques to fabricate chicken feet leather without the need for traditional stitching. Drawing inspiration from the papier-mâché process, we have created a method we call Cuir Mâché, allowing the small hides to be transformed into final 3D objects.

cuir mâché

Chicken skin is the only livestock hide not commonly used for leather, primarily due to its small size. This project seeks to challenge that limitation by exploring innovative ways to create leather from chicken feet—a valuable but often overlooked waste stream in the poultry industry. By repurposing this material, we aim to reduce waste and offer a sustainable alternative. We have developed two unique techniques to fabricate chicken feet leather without the need for traditional stitching. Drawing inspiration from the papier-mâché process, we have created a method we call Cuir Mâché, allowing the small hides to be transformed into final 3D objects.

cuir mâché

Chicken skin is the only livestock hide not commonly used for leather, primarily due to its small size. This project seeks to challenge that limitation by exploring innovative ways to create leather from chicken feet—a valuable but often overlooked waste stream in the poultry industry. By repurposing this material, we aim to reduce waste and offer a sustainable alternative. We have developed two unique techniques to fabricate chicken feet leather without the need for traditional stitching. Drawing inspiration from the papier-mâché process, we have created a method we call Cuir Mâché, allowing the small hides to be transformed into final 3D objects.

Chicken Feet Bag

Chicken skin is the only livestock hide not commonly used for leather, primarily due to its small size. This project seeks to challenge that limitation by exploring innovative ways to create leather from chicken feet—a valuable but often overlooked waste stream in the poultry industry. By repurposing this material, we aim to reduce waste and offer a sustainable alternative. We have developed two unique techniques to fabricate chicken feet leather without the need for traditional stitching. Drawing inspiration from the papier-mâché process, we have created a method we call Cuir Mâché, allowing the small hides to be transformed into final 3D objects.

cuir mâché

Chicken skin is the only livestock hide not commonly used for leather, primarily due to its small size. This project seeks to challenge that limitation by exploring innovative ways to create leather from chicken feet—a valuable but often overlooked waste stream in the poultry industry. By repurposing this material, we aim to reduce waste and offer a sustainable alternative. We have developed two unique techniques to fabricate chicken feet leather without the need for traditional stitching. Drawing inspiration from the papier-mâché process, we have created a method we call Cuir Mâché, allowing the small hides to be transformed into final 3D objects.

cuir mâché

Chicken skin is the only livestock hide not commonly used for leather, primarily due to its small size. This project seeks to challenge that limitation by exploring innovative ways to create leather from chicken feet—a valuable but often overlooked waste stream in the poultry industry. By repurposing this material, we aim to reduce waste and offer a sustainable alternative. We have developed two unique techniques to fabricate chicken feet leather without the need for traditional stitching. Drawing inspiration from the papier-mâché process, we have created a method we call Cuir Mâché, allowing the small hides to be transformed into final 3D objects.

cuir mâché

Chicken skin is the only livestock hide not commonly used for leather, primarily due to its small size. This project seeks to challenge that limitation by exploring innovative ways to create leather from chicken feet—a valuable but often overlooked waste stream in the poultry industry. By repurposing this material, we aim to reduce waste and offer a sustainable alternative. We have developed two unique techniques to fabricate chicken feet leather without the need for traditional stitching. Drawing inspiration from the papier-mâché process, we have created a method we call Cuir Mâché, allowing the small hides to be transformed into final 3D objects.

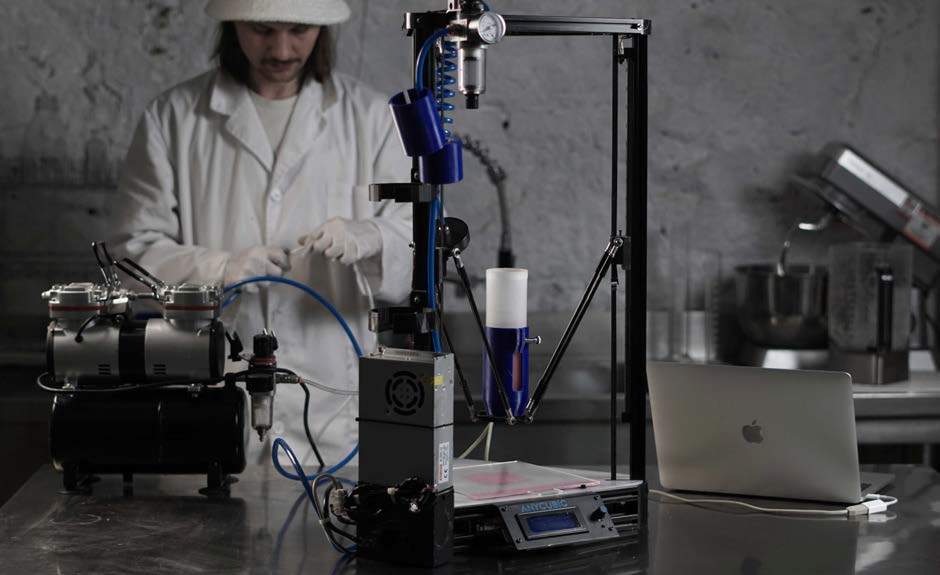

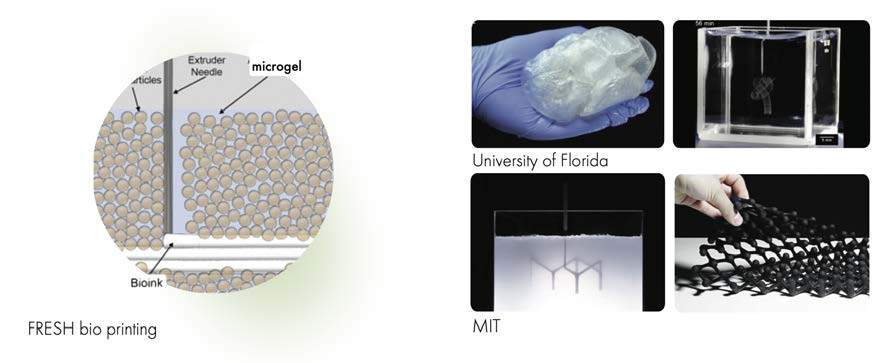

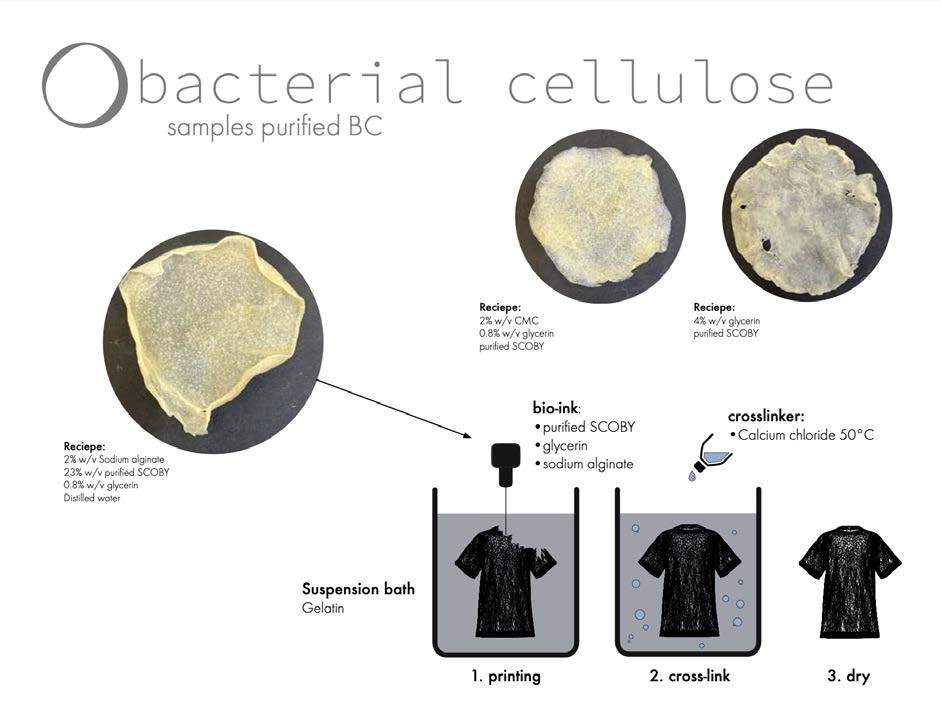

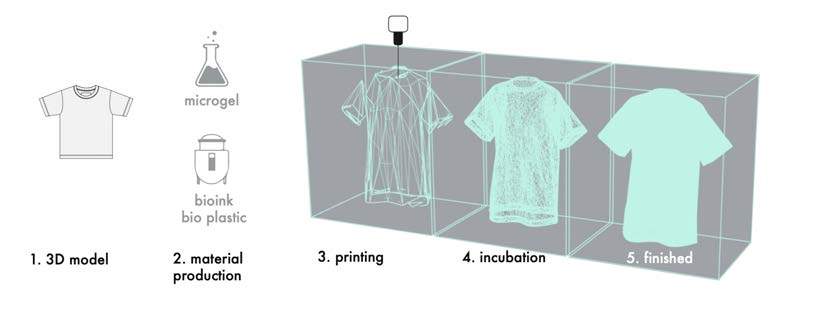

Amass: Bioprinting Bacterial Cellulose

A research project that investigates how bioprinting bacterial cellulose can be used to tackle the root of the problem with today’s supply chain in fashion, the assembly type of manufacturing. What if we instead could create distributed networks of designers and consumers growing garments straight from raw material to finished product?

Amass: Bioprinting Bacterial Cellulose

A research project that investigates how bioprinting bacterial cellulose can be used to tackle the root of the problem with today’s supply chain in fashion, the assembly type of manufacturing. What if we instead could create distributed networks of designers and consumers growing garments straight from raw material to finished product?

Amass: Bioprinting Bacterial Cellulose

A research project that investigates how bioprinting bacterial cellulose can be used to tackle the root of the problem with today’s supply chain in fashion, the assembly type of manufacturing. What if we instead could create distributed networks of designers and consumers growing garments straight from raw material to finished product?

Amass: Bioprinting Bacterial Cellulose

A research project that investigates how bioprinting bacterial cellulose can be used to tackle the root of the problem with today’s supply chain in fashion, the assembly type of manufacturing. What if we instead could create distributed networks of designers and consumers growing garments straight from raw material to finished product?

Amass: Bioprinting Bacterial Cellulose

A research project that investigates how bioprinting bacterial cellulose can be used to tackle the root of the problem with today’s supply chain in fashion, the assembly type of manufacturing. What if we instead could create distributed networks of designers and consumers growing garments straight from raw material to finished product?

Bioprinted Tshirt

Amass: Bioprinting Bacterial Cellulose

A research project that investigates how bioprinting bacterial cellulose can be used to tackle the root of the problem with today’s supply chain in fashion, the assembly type of manufacturing. What if we instead could create distributed networks of designers and consumers growing garments straight from raw material to finished product?

Night Plants

In the “Night Plants” painting, I explore the connection between plant life and the hidden processes that occur beneath the surface, much like the mycelial networks that weave through the natural world. This mirrors the concept of metempsychosis: the cyclical journey of life, death, and transformation. While what we see above ground may seem still, there's an ongoing process of creation and regeneration happening out of sight, just like mycelium breaking down and giving rise to new life. It speaks to the idea of reconnection with our environment through the unnoticed or hidden aspects of nature. The contrast between the dark blues and greens of the foliage and the softer, earthy pinks below suggests that life is constantly evolving, even in the quietest moments. In this way, the painting is a reflection of how art (like mycelium) can connect us to both the visible and the invisible, the known and the unknown, and how life continuously transmigrates through different forms.

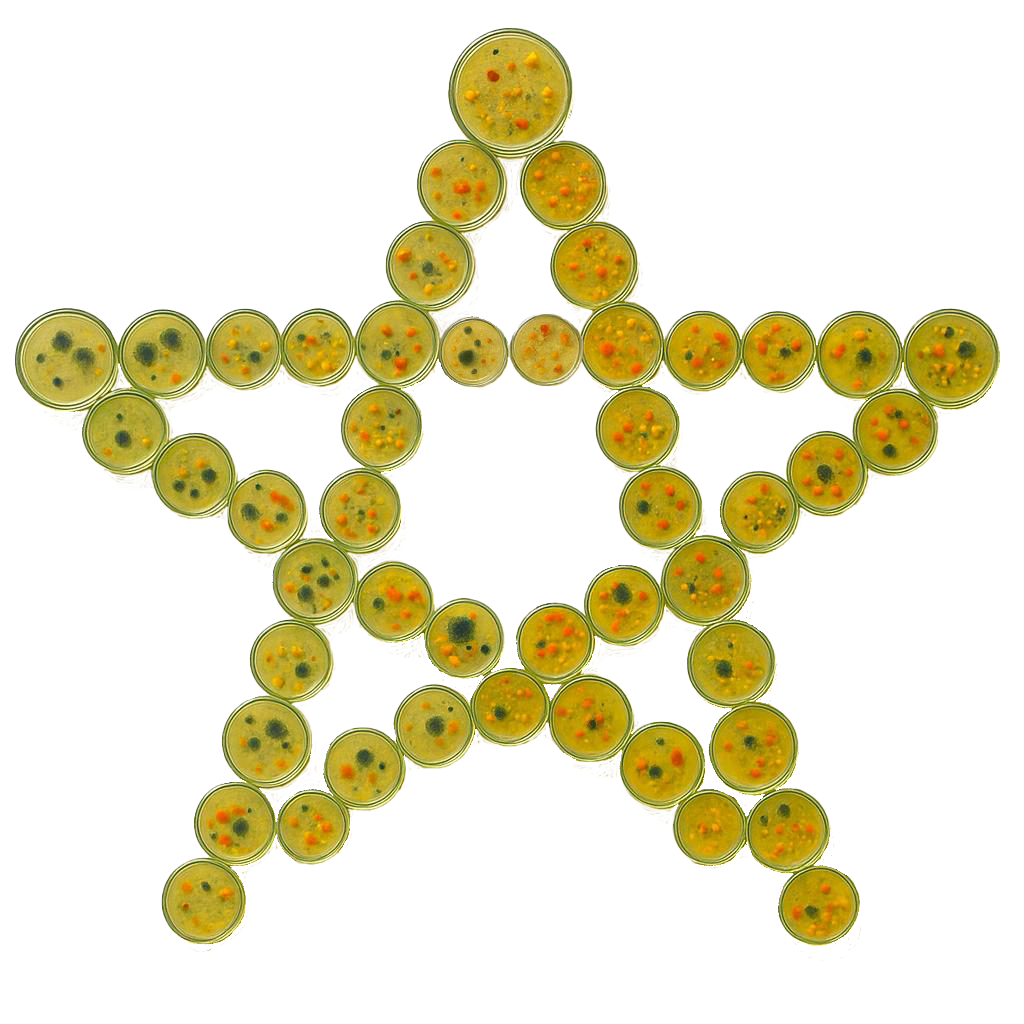

SCOBY Microbial Morphologies

Single colonies of bacteria and yeasts extracted from a SCOBY collected by a producer in Berlin grown on agar medium, 2023

Growing Biomaterials with plants and microbes with-in Berlin

3D scanned samples of foraged plants (Tree of Heaven, Ground Elder, Armenian Blackberry, Sea Buckthorn, Elderflower, Rosehip), SCOBY contained in a bottle, experiment with growing SCOBYs in 6-wells Petri dishes, solid SCOBY foam samples (from Kombucha SCOBY collected from producer in Berlin grown with tea infusion Rewe Bio; from Mirabelle plum's vinegar culture collected in Nauen and raw Elder fruits grown in Friedrichshain; from apple vinegar (Dennre) culture and raw elder flowers collected in Friedrichshain), placed on a bench at the microbiology laboratory of the Hengge Group, Department of Biology, Faculty of Life Sciences, HU Berlin, October 2025.

Growing Biomaterials with plants and microbes with-in Berlin

Edible plant samples and derived liquid ingredients, dry pellicles grown in comparative experiments, wet pellicles and inocula of a mixed culture of bacteria and yeasts (SCOBY) and of a single Gluconacetobacter hansenii bacterial strain, 2024.

WILD FOAMS

Solid SCOBY foam samples from the top: from Kombucha SCOBY collected from producer in Berlin grown with tea infusion Rewe Bio; from apple vinegar (Dennre) culture and raw elder flowers collected in Friedrichshain), from Mirabelle plum's vinegar culture collected in Nauen and raw Elder fruits grown in Friedrichshain, 2024-25.

SCOBY foam samples

3D scanned samples of solid SCOBY foam samples (from Kombucha SCOBY collected from producer in Berlin grown with tea infusion Rewe Bio; from Mirabelle plum's vinegar culture collected in Nauen and raw Elder fruits grown in Friedrichshain; from apple vinegar (Dennre) culture and raw elder flowers collected in Friedrichshain), placed on a bench at the microbiology laboratory of the Hengge Group, Department of Biology, Faculty of Life Sciences, HU Berlin, October 2025.

Foraging Rosehips

Author foraging rosehips in Volkspark Friedrichshain, August 2024

Foraging Linden flowers

Author foraging Linden flowers in Treptower Park, June 2024

T⊙TEMS by Tanja Vujinovic

T⊙TEMS Totems are vertical, floating avatars inhabiting the AvantGarden Spheres as hybrid nodes of consciousness. Their forms merge abstract, biomorphic, and techno-organic features, ranging from near-human to fully synthetic. They drift, hover, and oscillate, marking liminal zones and thresholds across virtual and gallery spaces. As inhabitants of the Zone of Encounter, they define vertical axes and invite visitors to explore space, and interact in novel ways. Each Totem is a layered presence—a vertical guardian bridging digital environments, exploratory play, and immersive soundscapes. These forms draw inspiration from totemic sculptures of indigenous cultures and shamanic ritual poles, which historically mark thresholds, liminal spaces, or nodes of presence. The vertical, stacked, and segmented structures echo these ceremonial objects while reinterpreted as floating techno-organic beings in digital environments.

Fungi-Fi

FUNGI-FI 2022 mixed media installation video full HD 1’ 02’’, poster 70x100cm, potted plants Fungi-Fi is a fake brand and product launch event that projects into our post-truth present a revolutionary, seemingly saving invention that looks like something out of a sci-fi movie. In fact, Fungi-Fi has the traits of an ecological dystopia, a possible future in the Anthropocene in which humanity solves CO2 emissions by enslaving the entire plant kingdom to guarantee itself a super internet connection. How? Inventing a wi-fi capable of picking up the electrical impulses of the Wood Wide Web, thus connecting to such an internet of the woods, the mycorrhizal network discovered by Suzanne Simard. With persuasive and emphatic language typical of advertising storytelling, Fungi-Fi aims to reflect on the human-nature relationship as a function of techno-scientific progress. Highlighting both humanity’s anthropocentric vice of thinking of the environment only as a resource to be exploited and the mania to commodify every knowledge, thing and creature for evergreen consumerism.

Chaotic Paradise

Year : 2022 Colour: B&W Dimensions:1920x1080 Duration: 02:00 Music: Ehsan Masoudian Country of Production: Iran In the duality of life, each mind perceives beauty differently. One person may even perceive deformity, whereas another is sensible of beauty. You can still sense The Garden of Eden with the fragrance of its flowers but it has lost its sense of familiarity. The Garden metaphorically represents our minds and way of thinking in pairs of opposites. Chaos implies the existence of unpredictable or random behaviour but in most cases, it is associated with undesirable disorganization or confusion. Fractal dimensions are derived from certain key features of fractals: self-similarity and irregularity. This fractal video art explores a chaotic paradise and how we descend into a dualistic world after the fall. As you watch the video, you are taken to a world you have never been to before and yet resonate with places you have seen in nature that are still unfamiliar to you. Consequently, the video has a sense of uncanny, of knowing and not knowing, and of wanting to explore its surroundings. In it, a utopia is portrayed that might fall victim to internal glitches. I used 3D scanning of a flower bouquet to create this video art. Bio: Arezou Ramezani is a London-based Iranian visual artist and podcaster (@arezouart). Having pursued two masters in Animation, Arezou loves to use different mediums and her work has been exhibited worldwide. She believes sharing emotions is essential that’s why she investigates the human's rawest feelings through her art where she conveys emotion and evokes a feeling in the audience. In her ink paintings, she gets inspired by music, human emotions and her own experiences where she expresses herself by drawing figures and portraits through hatched black ink lines that are in the juxtaposition of fluid colourful inks. She believes humans go through common experiences and art is the language we all understand and that's why in her art she tries to connect to the deeper layers of inner feelings of the audience and hopes they resonate with them.

THAT FEELING

An ode to the beauty of digital imperfection, where the glitch is not a mistake but an artistic language that transforms the familiar into the extraordinary. Each scene, although chaotic and fragmented, maintains a fragment of recognizability that keeps us hooked, while the mind tries to decipher the incomprehensible. Matteo Campulla (Iglesias, Sardinia -1982) is an interdisciplinary artist operating at the edges of image and language, dissecting their ruins. Through digital media, glitch art, and textual manipulations, he constructs visual and narrative environments where machines break down and errors become language. His work moves across textual performances, video art, and unstable archives, aiming not to restore but to amplify the noise of fractures: every fragment, every interference stands as evidence of an inevitable collapse. He does not seek answers: he generates collective hallucinations, inducing short circuits. He lives and works in Milan, where he continues to sabotage the margins of language and image.

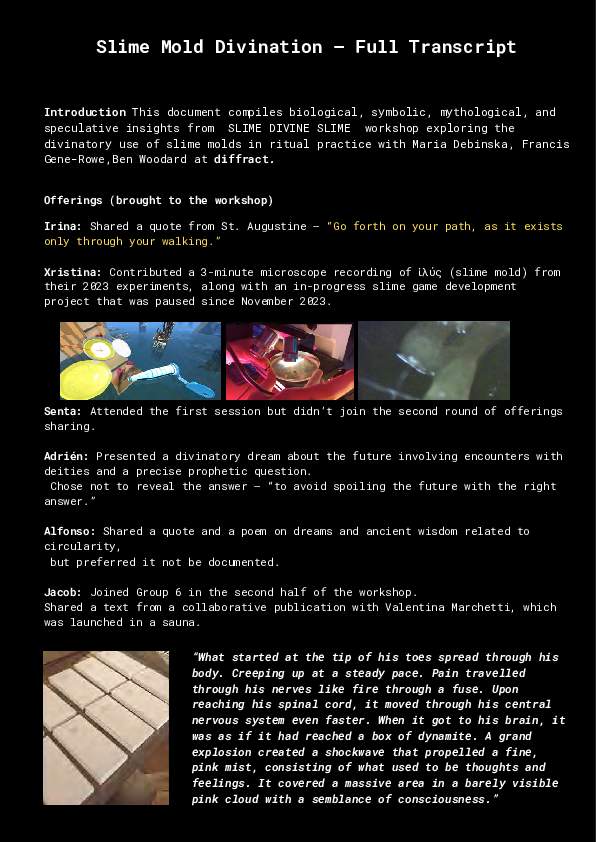

SLIME DIVINE SLIME

The document explores the symbolic, biological, and mythological significance of slime molds in divination practices, incorporating insights from a workshop on the topic. Slime Mold Divination Workshop Overview The workshop explored the intersection of slime molds, divination practices, and cultural anthropology through collaborative activities and discussions. - Participants included Maria Dębińska, Francis Gene-Rowe, and others. - The workshop featured individual and group sessions focusing on biological, symbolic, and mythological insights related to slime molds. - Various offerings were shared, including quotes, dreams, and artistic contributions. Biological Classification of Slime Molds This section detailed the scientific classification and characteristics of slime molds. - Slime molds are eukaryotic organisms classified under Kingdom Protista. - They differ from fungi by lacking chitin in their cell walls and can move in their plasmodial stage. - They are traditionally categorized as Myxogastria (true slime molds) within Protista. Mythological and Symbolic Connections The workshop examined ancient and modern interpretations of slime molds in myth and folklore. - Ancient Greek philosophers associated slime with the life force and primordial matter. - Alchemical traditions viewed slime-like substances as the raw material for transformation. - Modern speculative fiction often portrays slime molds as symbols of collective intelligence and organic problem-solving. Exquisite Corpse Collaborative Drawing Participants engaged in a surrealist drawing exercise to explore themes of slime and divination. - The drawing was divided into three sections: celestial ooze, conflict and flow, and twin fires of passion and memory. - Each section represented different interpretations of growth, transformation, and reflection. - The collective drawing served as a basis for a mycomantic reading, interpreting slime mold patterns as omens. Divination Practices and Slime Mold Research This section highlighted the integration of slime molds into divination practices and research methodologies. - Maria Dębińska presented her work on slime molds as collaborators in ritual knowledge systems. - The divination toolkit included a pentagram, I Ching, and slime mold growth cycles. - The session emphasized the participatory nature of slime molds in divination, blurring the lines between computation and interpretation. Generative Oracle Practice with Slime Molds Participants combined various divination systems to create a generative oracle practice. - The process involved interpreting slime mold movement through symbolic frameworks. - Key concepts included improvisation, entanglement, and non-linear storytelling. - The final oracle readings reflected a journey of transformation and memory, emphasizing the dynamic nature of slime molds. Final Reflections and Interpretations The workshop concluded with reflections on the implications of slime molds in understanding life and divination. - Participants discussed the evolutionary significance of slime molds as early eukaryotic life forms. - The concept of slime as a pre-god condition was explored, emphasizing its role in the emergence of life and narrative. - The workshop highlighted the importance of time, memory, and the organic processes of divination in contemporary practices.

Petristar

PetriStar

Slime and emergent networks. Meditations on sluggish movement

SLIME AND EMERGENT NETWORKS

The slime mould behaves intelligently but its behaviours are not conscious; they result from a system of complex oscillations within the cell, which propel the cytoplasm in certain directions: towards attractant substances and away from repellents. In this case, thinking without a (nervous) system literally means going with the flow (of cytoplasm).

SLIME AND EMERGENT NETWORKS

The patterns and fluctuations of Physarum’s movements cannot be discerned with a naked eye, but are easily captured by means of time-lapse photography. The slime mould operates in a temporality adjacent to our own; it is just slightly too slow for its movements to be perceptible in real time by a human eye, but fast enough to surprise us with sudden expansions or attempts to escape from its Petri dish. It leaves us with the uncanny feeling that it only moves when we look the other way.

SLIME AND EMERGENT NETWORKS

The time-lapse is a technique of modelling the movements of Physarum (by setting up different snapshot intervals different images are obtained) as much as representing them. It captures the fluctuations of the slime mould’s internal cytoplasmic streams and reveals the stunning diversity of its morphology, which imposes on a human observer an anthropomorphic hermeneutic, inviting us to interpret them as moments of hesitation, grasping, climbing, waving, and pulsating. The slime mould comes alive through those images and acquires human-like characteristics. It is difficult not to read intentions, decisions and consciousness into its behaviour; the blob acquires a personality.

SLIME AND EMERGENT NETWORKS

When it reaches a point when a decision about the direction of its further movement has to be made, Physarum slows down to take in the necessary information (through a chemical sensing process called chemotaxis). The slime mould moves in tune with the chemical signals it receives from the environment, it is the time-lapses that produce an illusion of consciousness. From the slime mould’s perspective, consciousness would corrupt the thinking; deliberation blocks the flow.

SLIME AND EMERGENT NETWORKS

Even though the slime mould does not plan it is used in network planning and optimisation. The smooth and spontaneous flow of cytoplasm is abstracted into network graphs and algorithms. The word network used to mean the fishnets woven by fishermen to catch fish and other sea creatures; a filtering tool whose function was to separate, not connect. Today networks mean tools for connection - what started as a metaphor based on similarity of shapes, became a social reality of instant connectivity mediated by various telecommunication technologies. The ideology of networks is entirely divorced from their etymology: since networks became the new architecture of power and control, nothing should slip through the cracks of seamless and universal communication. What if we took Physarum as a model for unpremeditated collective movement instead of networks?

SLIME AND EMERGENT NETWORKS

When the first telegraph networks were laid at the bottom of the Atlantic their contemporaries described them as a global brain; the idea of global connectivity immediately inspired the thought of an emergent global consciousness. At the same time, the slime that covered the first transatlantic telegraph cables posed crucial philosophical problems and inspired the concept of protoplasm - primordial slime, the source of all life and thinking. Since then slime has posed questions that can be solved both by means of mathematics and metaphysics, which in this case are the same thing. What started as a sturdy network of telegraph and then telephone cables became wireless and provided the illusion of immateriality and immediacy. But just as fishnets dropped into the marine depths always carry the possibility of encountering unknown creatures never seen before, the mysticism of communication networks remains hidden at the bottom of the sea, in the optic cables that span the globe.

SLIME AND EMERGENT NETWORKS

SLIME FICTIONS

A black surface is covered in white dots. In the centre one bigger yellow dot starts growing and spreading in all directions, covering the territory in yellowish translucent film, then contracting to form a network of yellow tubes between the dots. A map emerges, which is a fairly precise representation of the Tokyo suburban railway network. The dots are oat flakes. The black surface is agar. The yellow thing is the slime mold Physarum polycephalum, known for its ability to create efficient networks of protein tubes connecting its food sources. Once we know that what we are seeing is a map of towns around Tokyo, the image becomes rather sinister to watch; the spreading Physarum resembles a tsunami wave or a nuclear explosion. Then, a network appears that connects the towns while the rest of the territory remains covered in slime - Physarum’s external memory, a map of the territory already explored. The whole scene could be a part of a science fiction scenario in which an intelligent alien blob invades the Earth, rampages it in search of resources and creates a very efficient network for extracting and transporting them, obliterating all terrestrial life in the process. (The movie of Fig 1 of the paper: Atsushi Tero, et al. Science 327, 439 (2010). The experiment was performed by Seiji Takagi. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BZUQQmcR5-g)

SLIME FICTIONS

The connection between numbers and the natural world is both mysterious and ancient and serves as the foundation of various divination systems. But are divination and computation related because they both deal with numbers, or do they emerge organically from living systems themselves? Physarum’s ability to compute paths, connections and future possibilities turns it into a storytelling device and a screen for human projections. Slime mold networks embody the strange convergence of abstract numbers and organic matter, where computation and storytelling converge.

Slime Mold Beetles

The family Sphindidae, commonly known as the Cryptic Slime Mold Beetles, comprises 67 species divided among 9 genera and 4 subfamilies. Sphindidae is represented in all major zoogeographic regions. All known species are myxomycophagous (eat slime molds).

Physarum Polycephalum

Physarum polycephalum is a plasmodial slime mould, an organism that looks like a fungus but behaves like an animal, as it is able to move and feeds on bacteria, fungi spores, and rotting matter. Its unusual properties have turned it into a very popular laboratory organism, employed in a variety of experiments investigating the origins of intelligence and consciousness, as well as the creation and optimization of networks.

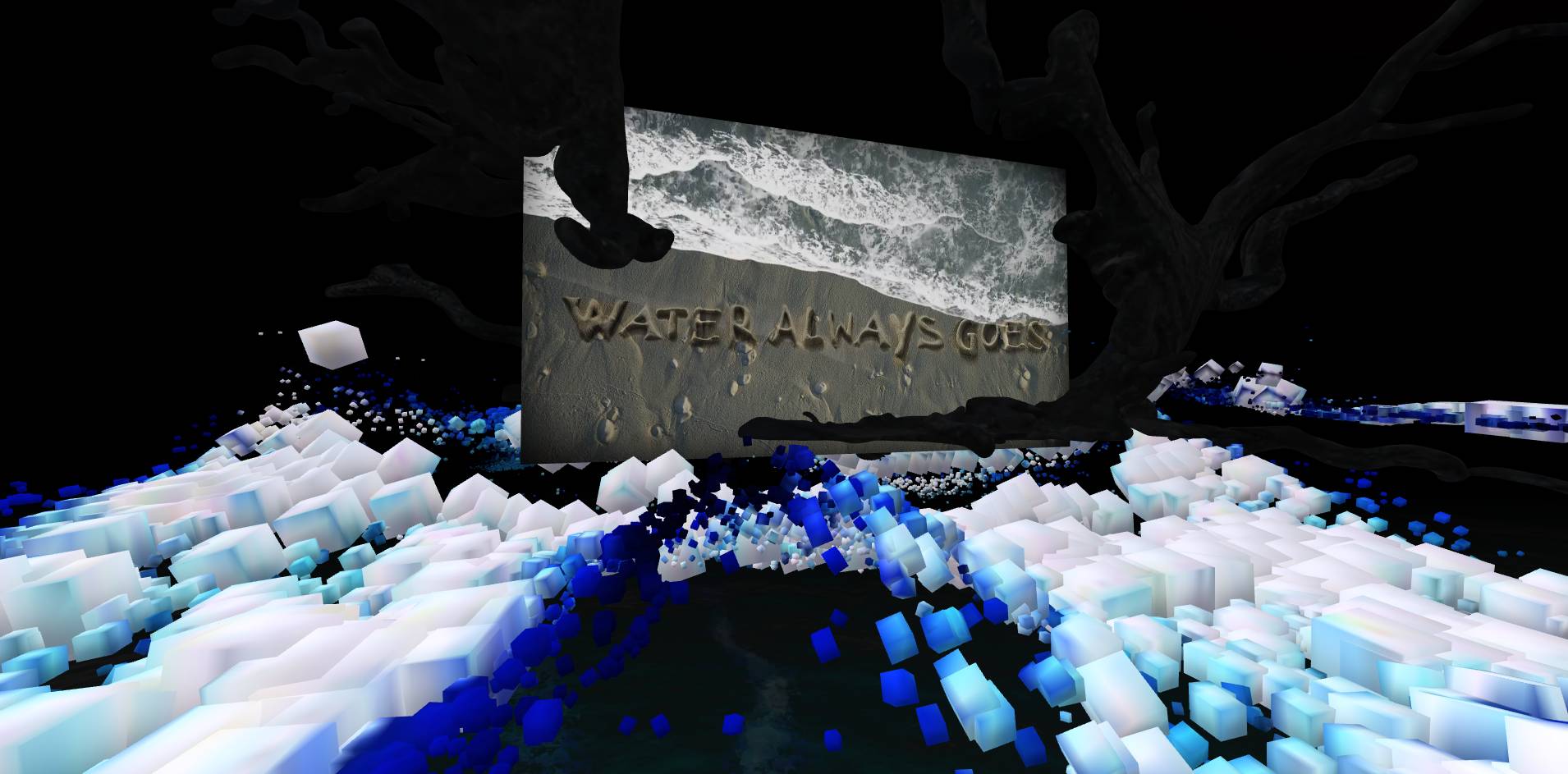

Water Always Goes Where It Wants to Go

“Water Always Goes Where It Wants to Go” is an ecoperformance video of the body in synergy with the storied landscape of water. How can we go back to something we already have? We are born out of water, and water constitutes our body, our territories, and our myths. Mapping water through the body, in between transitory space for waters, the short film investigates the relationship between the self, its embodied and somatic dialogues, and these physical and symbolic waters, questioning how we can return to our first water, the common body. Ecoperformance conceives landscapes as bodies, an extension of ancestral mythical understanding of environment embodiment using motion capture and personification of water. Just as water which has no form can give form to everything, motion of the body can give form to space. Alina Tofan’s movement was motion captured, creating corporealities of the common body of water. As Alina performs, she transforms her consciousness to become water in its various states, investigating how water incarnates human beings in the first person discourse, an embodiment, from the individual “one” to the intertwined collective One, bound by water. Artistic concept: Yiou Wang & Alina Tofan Direction & Scenography: Yiou Wang Motion Capture Ecoperformance: Alina Tofan Sound Design: Ștefan Blănică Produced by: Mixanthropy Art Tech Studio & Plastic Art Collective External Links: https://plasticartperformance.org/ https://yiouwang.org/

Water Always Goes Where It Wants to Go

“Water Always Goes Where It Wants to Go” is an ecoperformance video of the body in synergy with the storied landscape of water. How can we go back to something we already have? We are born out of water, and water constitutes our body, our territories, and our myths. Mapping water through the body, in between transitory space for waters, the short film investigates the relationship between the self, its embodied and somatic dialogues, and these physical and symbolic waters, questioning how we can return to our first water, the common body. Ecoperformance conceives landscapes as bodies, an extension of ancestral mythical understanding of environment embodiment using motion capture and personification of water. Just as water which has no form can give form to everything, motion of the body can give form to space. Alina Tofan’s movement was motion captured, creating corporealities of the common body of water. As Alina performs, she transforms her consciousness to become water in its various states, investigating how water incarnates human beings in the first person discourse, an embodiment, from the individual “one” to the intertwined collective One, bound by water. Artistic concept: Yiou Wang & Alina Tofan Direction & Scenography: Yiou Wang Motion Capture Ecoperformance: Alina Tofan Sound Design: Ștefan Blănică Produced by: Mixanthropy Art Tech Studio & Plastic Art Collective External Links: https://plasticartperformance.org/ https://yiouwang.org/

BALANCE IS FOR GODS

*Cosmic Perspective 1.Who can judge the future? From a cosmic perspective, the future is vast, indifferent, and shaped by universal forces. Stars will die; galaxies will collide. Judgment is irrelevant on this scale. 2.Who can judge the past? The past is written in stardust, in the cosmic microwave background, in the light of distant stars. It is observed but not judged. 3.Whose knowledge matters? Cosmic knowledge humbles us, reminding humans of their smallness and the importance of fostering life on this fragile planet. **Geological Perspective (Rocks, Mountains, Earth’s Crust) 1.Who can judge the future? Geological timeframes dwarf human concerns. From this perspective, the future unfolds in millions of years. Mountains erode; tectonic plates shift. The focus is on inevitability rather than judgment. 2. Who can judge the past? Rocks hold the record of Earth’s history—volcanic eruptions, sedimentary layers, fossilized life. They silently testify to what has been without moral judgment. 3. Whose knowledge matters? Geological knowledge matters because it reveals the long-term impacts of processes like erosion, fossilization, and climate shifts, helping us understand deep time. ***Ecosystem or Gaia Perspective 1.Who can judge the future? From a planetary or ecosystem perspective, the future is not about judgment but about maintaining balance. Feedback loops—like climate regulation or biodiversity thresholds—are the metrics by which the future is assessed. 2.Who can judge the past? Ecosystems judge the past by the stability they inherit. Extinctions, pollution, and habitat loss echo as disruptions that shape resilience or fragility. 3.Whose knowledge matters? The ecosystem perspective values collective knowledge. The interplay of all species and processes contributes to the health of the whole. ****Rivers, Oceans, or Watersheds’ Perspectives 1.Who can judge the future? For rivers and oceans, the future is about flow and continuity. Dams, pollution, and climate change are disruptions to this natural flow, and they judge the future by whether it allows life to thrive. 2.Who can judge the past? Rivers carve the past into landscapes, and oceans hold records of Earth's climate history in their depths. These perspectives “judge” based on the patterns left behind—eroded shorelines or coral reef bleaching. 3.Whose knowledge matters? Hydrological cycles teach us the value of interconnected systems. The knowledge of water—its movement, storage, and transformation—matters for all life. *****Microbial Perspectives: 1. Who can judge the future? Microbes, as the foundation of life, may see the future as a web of potentialities. Their role in cycles like nitrogen fixation and digestion suggests that the future is built one interaction at a time. 2. Who can judge the past? For microbes, the past might be stored in genetic material—an evolutionary record of survival strategies. They show that the past matters insofar as it provides solutions to current and future challenges. 3. Whose knowledge matters? Microbial knowledge is unseen but essential. It reminds us that the smallest contributors to ecosystems often have the most profound impact. ******Plants’ Perspectives 1.Who can judge the future? Plants might view the future through growth and reproduction cycles, judging it by the availability of sunlight, water, and nutrients. For them, future viability depends on ecological balance and the continuity of conditions. 2.Who can judge the past? The past is etched into growth rings, soil conditions, and genetic diversity. Plants could “judge” the past based on how well ecosystems have nurtured biodiversity and resilience. 3.Whose knowledge matters? Plants exemplify the importance of slow, incremental knowledge—adapting over millennia. They remind us that patient, long-term thinking can sustain life. *******Fungi's Perspective: 1.Who can judge the future? Fungi would likely view the future as a networked, interconnected possibility rather than something to be judged. Their mycelial networks function by adapting to environmental signals, emphasizing collaboration and mutualism over judgment. 2.Who can judge the past? For fungi, the past is embedded in the soil, the decaying organic matter they recycle. Instead of judgment, fungi interpret the past through decomposition and transformation, turning history into nourishment for future growth. 3.Whose knowledge matters? Fungi might argue that all knowledge matters, especially the knowledge that arises from symbiotic relationships. They demonstrate that knowledge is distributed across networks, not centralized in any single organism or species. ********Animals' Perspectives 1.Who can judge the future? Animals often operate in cycles and rhythms tied to their immediate environments. They might view the future not as an abstraction but as a continuation of lived experience—inseparable from their habitat’s health and stability. 2. Who can judge the past? From animals’ perspectives, the past is written into instinct and memory. They embody past lessons through evolved behaviors and survival strategies, emphasizing adaptation rather than judgment. 3. Whose knowledge matters? Animal knowledge is diverse and often context-specific. Migration paths, predator-prey dynamics, or social hierarchies demonstrate that localized, embodied, and intergenerational knowledge is invaluable. *********Indigenous or Ancestral Perspectives: 1.Who can judge the future? Indigenous knowledge systems often view the future as a continuation of ancestral responsibilities. The future is judged by how well it honors past teachings and ensures the well-being of generations yet to come. 2. Who can judge the past? The past is sacred, a source of wisdom and guidance. Mistakes are not to be judged harshly but to be learned from, ensuring balance and harmony are restored. 3. Whose knowledge matters? Indigenous perspectives emphasize relational knowledge—between people, land, and non-human beings. All knowledge is interdependent and holds value in sustaining life. **********AI or Technological Perspectives 1. Who can judge the future? AI might judge the future based on data and optimization. It would focus on predictive models and maximizing outcomes rather than emotional or moral judgment. 2. Who can judge the past? The past is a dataset to analyze. Patterns, errors, and trends are examined for insights into improving future decisions. 3. Whose knowledge matters? From a technological perspective, data-driven knowledge matters most—but this raises ethical questions about who controls the data and whose narratives are included. Additional Questions Humans Could Reflect On: 1. What does it mean to belong to a system greater than ourselves? Inspired by rivers, mountains, and stars, this question emphasizes humility and interconnectedness. 2.How can we integrate different temporalities (short-term vs. long-term thinking)? Fungi, mountains, and the cosmos challenge humans to think beyond immediate concerns. 3. What role does reciprocity play in knowledge and judgment? Indigenous systems and bees teach the importance of mutual benefit and balance. 4. How can we honor the unseen forces that sustain us? Microbes, fungi, and the microbiome reveal the invisible yet essential processes humans often overlook. 5. What is the cost of prioritizing human judgment over other forms of wisdom? Technology and ecosystems remind us that human-centric thinking can lead to imbalance and degradation. NATURAL BORN WASTERS Additional Questions Humans Could Ask Inspired by Fungi: -How can we cultivate symbiotic relationships with the environment? Inspired by fungi, humans might reflect on fostering mutualism rather than exploitation in their interactions with nature. -What does it mean to decompose ethically? Drawing from fungi's role in breaking down organic material, this question invites humans to think about their legacy and ecological impact. -How can networks of connection enhance resilience? Fungal networks highlight the power of interconnection. Humans might explore how collaborative systems can address environmental and societal challenges. -What lessons can we learn from decay and regeneration? Observing how fungi transform the old into the new could prompt humans to reconsider waste, renewal, and sustainability. -What is the role of humility in hybrid ecosystems? Fungi thrive through subtle, unseen work. Humans might ask how adopting humility could improve their stewardship of the Earth. -How can we measure success beyond growth? Inspired by fungi's role in maintaining equilibrium, humans could rethink metrics of success to include balance, diversity, and sustainability. MORE MORE-THAN-HUMAN QUESTIONS: 1.How do we define justice in non-human terms? 2.What does flourishing look like for ecosystems, not just humans? 3.What would a world without humans "say" about itself? 4.How can humans make decisions that honor all life forms? 5.What does it mean to listen to the Earth’s rhythms? BALANCE IS FOR GODS 1.The first humans were created by the gods to serve them and keep the world in balance. The first humans were perfect in every way, but they were also naïve and easily led astray. The gods grew tired of their shenanigans and decided to destroy them. 2.The second humans were created from the blood of the first humans. They were stronger and wiser, but still prone to error. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 3.The third humans were created from the clay of the earth. They were the first humans to be truly mortal. The gods gave them intelligence and the ability to reason, but they were also flawed and susceptible to temptation. 4.The fourth humans were created from the fire of the sun. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for evil. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 5.The fifth humans were created from the water of the sea. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for good. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 6.The sixth humans were created from the wind. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for both good and evil. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 7.The seventh humans were created from the sperm of the first humans. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for love. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 8.The eighth humans were created from the egg of the first humans. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for life. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 9.The ninth humans were created from the dust of the earth. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for death. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance. 10.The tenth humans were created from the breath of the first humans. They were the first humans to be born with the capacity for both life and death. The gods gave them free will, but also tasked them with the responsibility of keeping the world in balance.

The Mycomancer´s Oak

Inspired by the "Spirit in a Bottle" Tale: In this narrative, a gifted alchemist sets out on a daring journey to trap the very spirit that animates all living things—a luminous, elusive essence believed to be the quintessence of life. Armed with ancient knowledge and an unyielding ambition, he crafts a delicate glass bottle intended to serve as a vessel for this vital force. However, as the alchemist painstakingly distills natural elements and refines his process, he soon encounters an unexpected truth: the spirit is not a passive substance to be tamed and stored. It is a wild, dynamic energy that resists confinement, its essence forever in flux. The very moment it is sealed within the bottle, the spirit begins to challenge the boundaries of its transparent prison, stirring upheaval and transformation both within the vessel and in the world beyond. In the unfolding drama, the bottle comes to symbolize more than mere containment—it embodies human ambition, hubris, and the perennial struggle to impose order on the untamable forces of nature. The alchemist learns that true mastery does not lie in trapping the spirit, but rather in understanding and working with its ever-shifting nature. In letting go of the need to control, he finds a deeper harmony with the processes of transformation that govern life itself. The Message: The Greems Brothers’ “Spirit in a Bottle” is ultimately a parable about the limits of human control. It suggests that life’s most profound forces—its creativity, energy, and transformative potential—cannot be permanently confined or owned. Instead, they must be embraced in their fluidity, a reminder that our attempts to fix or capture the ever-changing spirit of existence may only lead to unintended consequences. In this way, the story invites us to recognize that true wisdom comes from working in tandem with nature’s rhythms, rather than trying to dominate them.