Art

City

Catalog view is the alternative 2D representation of our 3D virtual art space. This page is friendly to assistive technologies and does not include decorative elements used in the 3D gallery.

Mycohacking The Future

Spaces in this world:

Statement:

Mycohacking the Future

“Worms. Ants. Maggots. Beetles. Mushrooms. Death was almost the moment when life overflowed its cup. Death wasn’t the end of life. It was the end of the singular… Make me bigger than an ‘I’. Make me good soil.” — Sophie Strand

Mycohacking the Future is the third edition of an ongoing event series exploring fungi as collaborators in art, science, technology, and activism. Curated by Xristina Sarli and produced by TOP Lab (Berlin’s first DIY biolab and transdisciplinary community), the project interlaces exhibitions, talks, workshops, and performances in response to ecological crisis and the urgency of regenerative practices.

Using mycelium as both symbol and medium, artists and designers unearth its multi-layered meanings: a metaphor of connection, of decay as regeneration, and of interwoven processes that challenge the myth of human exceptionalism. Mycofabrication — the practice of producing ideas, materials, and objects in collaboration with fungi — demonstrates interspecies design where no human genius creates from nothing. Instead, the organism’s mind and needs shape the process, reminding us that creativity emerges in feedback loops across species.

In a time marked by ecocide, patriarchal capitalism, and extractivist economies, fungi offer a living model of resilience, cooperation, and transformation. This edition gathers international artists and researchers working with mycelium-based biomaterials, ephemeral media, and hybrid technologies. From mycelium leather in zero-waste fashion to VHS tapes re-coded by plastic-eating fungi, the works open critical questions about sustainability, decolonial post-capitalist futures, and the entanglement of human, nonhuman, and technological worlds.

The exhibition becomes a multispecies gathering, where each work transitions into another possibility — collective, cooperative, and driven by the urge to heal our futures together. Mycohacking the Future invites visitors to explore alternative perspectives on materiality and knowledge production, to experience art not as representation but as a living, evolving entity that transcends human narratives.

Curated by Xristina Sarli, Berlin DE

Alessandro Volpato, Alfie Greenwood, Benjamin Janzen, Emma Patmore, Fomes Fomentarius, Ganoderma Applanatum, Ganoderma Lucidum, Ganoderma Sessile, Jan Klappenecker, Karin Weissenbrunner, Maria Kobylenko, Mon Castillo, Mycohackers Berlin, Panelus Stipticus, Pestalotiopsis Microspora, Ulises Urra, Xristina Sarli

3D Environment Description:

Mycohacking the Future

“Worms. Ants. Maggots. Beetles. Mushrooms. Death was almost the moment when life overflowed its cup. Death wasn’t the end of life. It was the end of the singular… Make me bigger than an ‘I’. Make me good soil.” — Sophie Strand

Mycohacking the Future is the third edition of an ongoing event series exploring fungi as collaborators in art, science, technology, and activism. Curated by Xristina Sarli and produced by TOP Lab (Berlin’s first DIY biolab and transdisciplinary community), the project interlaces exhibitions, talks, workshops, and performances in response to ecological crisis and the urgency of regenerative practices.

Using mycelium as both symbol and medium, artists and designers unearth its multi-layered meanings: a metaphor of connection, of decay as regeneration, and of interwoven processes that challenge the myth of human exceptionalism. Mycofabrication — the practice of producing ideas, materials, and objects in collaboration with fungi — demonstrates interspecies design where no human genius creates from nothing. Instead, the organism’s mind and needs shape the process, reminding us that creativity emerges in feedback loops across species.

In a time marked by ecocide, patriarchal capitalism, and extractivist economies, fungi offer a living model of resilience, cooperation, and transformation. This edition gathers international artists and researchers working with mycelium-based biomaterials, ephemeral media, and hybrid technologies. From mycelium leather in zero-waste fashion to VHS tapes re-coded by plastic-eating fungi, the works open critical questions about sustainability, decolonial post-capitalist futures, and the entanglement of human, nonhuman, and technological worlds.

The exhibition becomes a multispecies gathering, where each work transitions into another possibility — collective, cooperative, and driven by the urge to heal our futures together. Mycohacking the Future invites visitors to explore alternative perspectives on materiality and knowledge production, to experience art not as representation but as a living, evolving entity that transcends human narratives.

Curated by Xristina Sarli, Berlin DE

Alessandro Volpato, Alfie Greenwood, Benjamin Janzen, Christos Kourtidis, Emma Patmore, Fomes Fomentarius, Ganoderma Applanatum, Ganoderma Lucidum, Ganoderma Sessile, Jan Klappenecker, Karin Weissenbrunner, Maria Kobylenko, Mon Castillo, Mycohackers Berlin, Panelus Stipticus, Pestalotiopsis Microspora, Ulises Urra, Xristina Sarli

Artworks in this space:

Curator´s Tour

Next Stream: Bioglitch Performance — 13 December 2025, Mycohacking the Future space Featuring Alexandra Maciá, Giorgio Alloatti, and Xristina Sarli. This live event merges sound, biofeedback, and code, using plastic-eating fungi to distort VHS and audio tape recordings composed of polyurethane — transforming synthetic waste into sonic and visual decay. Bioartist, XR artist, developer, and curator Xristina Sarli presents the works and research within each space of the PRIMA MATERIA Pavilion. The tour guides visitors through the interconnected worlds of Prima Materia, World Wide Waste, Decomposers, and Mycohacking the Future, unfolding how bioart, AI, and regenerative design intersect across the exhibition. In the coming months, a series of talks, performances, and workshops will be streamed directly from each pavilion space and announced both here and via TOP Lab’s website .

Myciliman

Ganoderma Sessille: wood-loving mycelium, polypore fungus Emma Patmore: artist, mycologist & organiser Mon Castillo: artist Moth larvae: insect Emma Patmore is an artist, mycologist & community organiser based in Berlin. She currently weaves the threads of collaboration, knowledge sharing and more-than materialism into projects like 90mil Art School and the Mycelionaires collective. Her work with mushrooms revolves around material experiments, multi-species agency & living sculptures.

Myko-Lab

Myko-Lab Participatory Biodesign and Biofabrication Mycelium is the vegetative part of a fungus that lies beneath the surface of the soil and consists of a dense network of hyphae—the long, branching, thread-like structures of a fungus. Mycelium feeds on plant-based organic matter and develops within it, creating a durable, composite material. Moreover, this material is fully compostable and can be returned to the soil, making the entire process of collection, creation, and disposal completely circular and ecological. Within the framework of the Industrial Design Laboratory at the Department of Interior Architecture, University of West Attica (UNIWA), Athens, Greece, students were asked to design equipment objects for an exhibition space using mycelium-based composite material. The project encouraged them to explore the material’s properties, its combination with other materials, the molding process, and sustainability aspects. Emphasis was placed on creativity, experimentation, and prototyping of the proposed objects. Through the course, students acquired theoretical knowledge about mycelium-based biomaterials and gained practical skills for developing sustainable products in the emerging field of bio-design. More specifically, the equipment objects were designed to serve four essential functions: signage, information display, stand, and seat. The photos depict images from the exhibition “Second Chance”, which took place in Athens in October 2024, where the fabricated mycelium objects were displayed both as artefacts and as functional equipment. The prototyping and fabrication process took place at UNIWA, where the molds were digitally fabricated using 3D printing and laser cutting tools, and manually assembled by the students. The molds were then filled with mycelium substrate, which was left to grow for one week. Finally, the mycelium objects were unmolded and left to dehydrate in open air under the Greek summer sun for another week. Overall, this project served as an introduction to bio-design and mycelium fabrication for more than 30 students who had the opportunity to design and grow their own mycelium-based objects. The main challenges involved controlling the mycelial growth process, addressing design resolution limitations, and managing the fabrication of molds. Despite these difficulties, the project successfully demonstrated the creative and ecological potential of mycelium as a sustainable design material, highlighting its role in shaping future practices in circular design and material innovation. Coordinator / Teaching assistant: Christos Kourtidis, PhD Candidate Supervising Professor: Panayotis Pangalos, Professor Participating Students: Sofia-Ioanna Alanioti, Androniki Balaska, Katerina Bechit, Rita Bechit, Konstantina Bekiari, Maria Dima, Efthymia Fouka, Aikaterini Garderi, Anastasia Gnatitsin, Dimitra Gonta, Nefeli Gralista, Lydia Karakala, Evangelia Konnari, Iliana Koukoutsi, Danai Kyriakopoulou, Aikaterini Lamprou, Maria Lazaridi, Alexandros Mantoudis, Irini Nikolopoulou, Nikolas Papadopoulos, Elena Papageorgiou, Antonia Preka, Vasileios, Efthymios Promponas, Theodora Regkoukou, Georgia Seranidi, Georgios Souliotis, Philisia-Maria Vassiliadi, Dimitrios Velentzas.

MYKOLAB

Myko-Lab Participatory Biodesign and Biofabrication Mycelium is the vegetative part of a fungus that lies beneath the surface of the soil and consists of a dense network of hyphae—the long, branching, thread-like structures of a fungus. Mycelium feeds on plant-based organic matter and develops within it, creating a durable, composite material. Moreover, this material is fully compostable and can be returned to the soil, making the entire process of collection, creation, and disposal completely circular and ecological. Within the framework of the Industrial Design Laboratory at the Department of Interior Architecture, University of West Attica (UNIWA), Athens, Greece, students were asked to design equipment objects for an exhibition space using mycelium-based composite material. The project encouraged them to explore the material’s properties, its combination with other materials, the molding process, and sustainability aspects. Emphasis was placed on creativity, experimentation, and prototyping of the proposed objects. Through the course, students acquired theoretical knowledge about mycelium-based biomaterials and gained practical skills for developing sustainable products in the emerging field of bio-design. More specifically, the equipment objects were designed to serve four essential functions: signage, information display, stand, and seat. The photos depict images from the exhibition “Second Chance”, which took place in Athens in October 2024, where the fabricated mycelium objects were displayed both as artefacts and as functional equipment. The prototyping and fabrication process took place at UNIWA, where the molds were digitally fabricated using 3D printing and laser cutting tools, and manually assembled by the students. The molds were then filled with mycelium substrate, which was left to grow for one week. Finally, the mycelium objects were unmolded and left to dehydrate in open air under the Greek summer sun for another week. Overall, this project served as an introduction to bio-design and mycelium fabrication for more than 30 students who had the opportunity to design and grow their own mycelium-based objects. The main challenges involved controlling the mycelial growth process, addressing design resolution limitations, and managing the fabrication of molds. Despite these difficulties, the project successfully demonstrated the creative and ecological potential of mycelium as a sustainable design material, highlighting its role in shaping future practices in circular design and material innovation. Coordinator / Teaching assistant: Christos Kourtidis, PhD Candidate Supervising Professor: Panayotis Pangalos, Professor Participating Students: Sofia-Ioanna Alanioti, Androniki Balaska, Katerina Bechit, Rita Bechit, Konstantina Bekiari, Maria Dima, Efthymia Fouka, Aikaterini Garderi, Anastasia Gnatitsin, Dimitra Gonta, Nefeli Gralista, Lydia Karakala, Evangelia Konnari, Iliana Koukoutsi, Danai Kyriakopoulou, Aikaterini Lamprou, Maria Lazaridi, Alexandros Mantoudis, Irini Nikolopoulou, Nikolas Papadopoulos, Elena Papageorgiou, Antonia Preka, Vasileios, Efthymios Promponas, Theodora Regkoukou, Georgia Seranidi, Georgios Souliotis, Philisia-Maria Vassiliadi, Dimitrios Velentzas.

DON´T

3D scanned fungal-composite door stopper Myko-Lab Participatory Biodesign and Biofabrication Mycelium is the vegetative part of a fungus that lies beneath the surface of the soil and consists of a dense network of hyphae—the long, branching, thread-like structures of a fungus. Mycelium feeds on plant-based organic matter and develops within it, creating a durable, composite material. Moreover, this material is fully compostable and can be returned to the soil, making the entire process of collection, creation, and disposal completely circular and ecological. Within the framework of the Industrial Design Laboratory at the Department of Interior Architecture, University of West Attica (UNIWA), Athens, Greece, students were asked to design equipment objects for an exhibition space using mycelium-based composite material. The project encouraged them to explore the material’s properties, its combination with other materials, the molding process, and sustainability aspects. Emphasis was placed on creativity, experimentation, and prototyping of the proposed objects. Through the course, students acquired theoretical knowledge about mycelium-based biomaterials and gained practical skills for developing sustainable products in the emerging field of bio-design. More specifically, the equipment objects were designed to serve four essential functions: signage, information display, stand, and seat. The photos depict images from the exhibition “Second Chance”, which took place in Athens in October 2024, where the fabricated mycelium objects were displayed both as artefacts and as functional equipment. The prototyping and fabrication process took place at UNIWA, where the molds were digitally fabricated using 3D printing and laser cutting tools, and manually assembled by the students. The molds were then filled with mycelium substrate, which was left to grow for one week. Finally, the mycelium objects were unmolded and left to dehydrate in open air under the Greek summer sun for another week. Overall, this project served as an introduction to bio-design and mycelium fabrication for more than 30 students who had the opportunity to design and grow their own mycelium-based objects. The main challenges involved controlling the mycelial growth process, addressing design resolution limitations, and managing the fabrication of molds. Despite these difficulties, the project successfully demonstrated the creative and ecological potential of mycelium as a sustainable design material, highlighting its role in shaping future practices in circular design and material innovation. Coordinator / Teaching assistant: Christos Kourtidis, PhD Candidate Supervising Professor: Panayotis Pangalos, Professor Participating Students: Sofia-Ioanna Alanioti, Androniki Balaska, Katerina Bechit, Rita Bechit, Konstantina Bekiari, Maria Dima, Efthymia Fouka, Aikaterini Garderi, Anastasia Gnatitsin, Dimitra Gonta, Nefeli Gralista, Lydia Karakala, Evangelia Konnari, Iliana Koukoutsi, Danai Kyriakopoulou, Aikaterini Lamprou, Maria Lazaridi, Alexandros Mantoudis, Irini Nikolopoulou, Nikolas Papadopoulos, Elena Papageorgiou, Antonia Preka, Vasileios, Efthymios Promponas, Theodora Regkoukou, Georgia Seranidi, Georgios Souliotis, Philisia-Maria Vassiliadi, Dimitrios Velentzas.

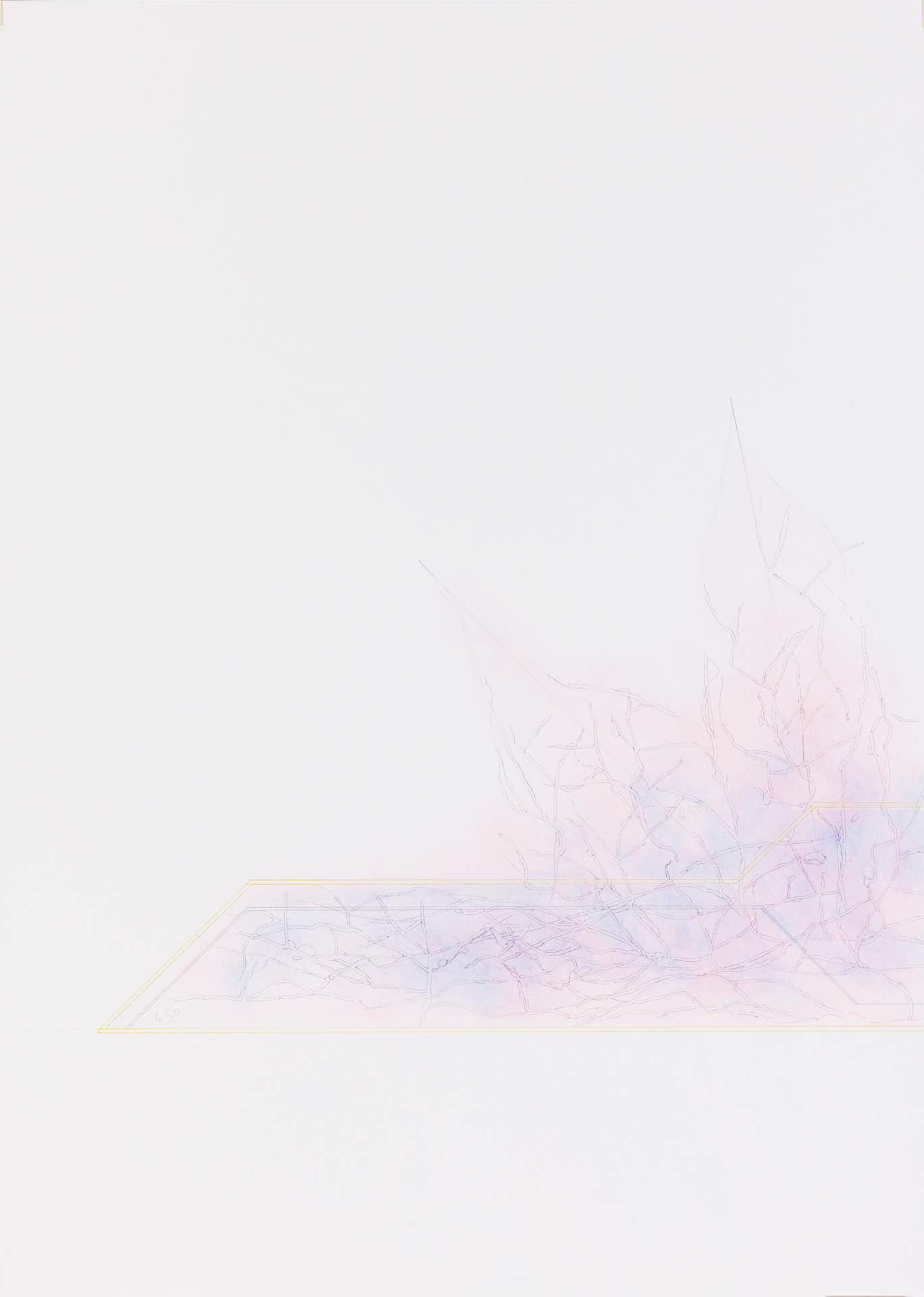

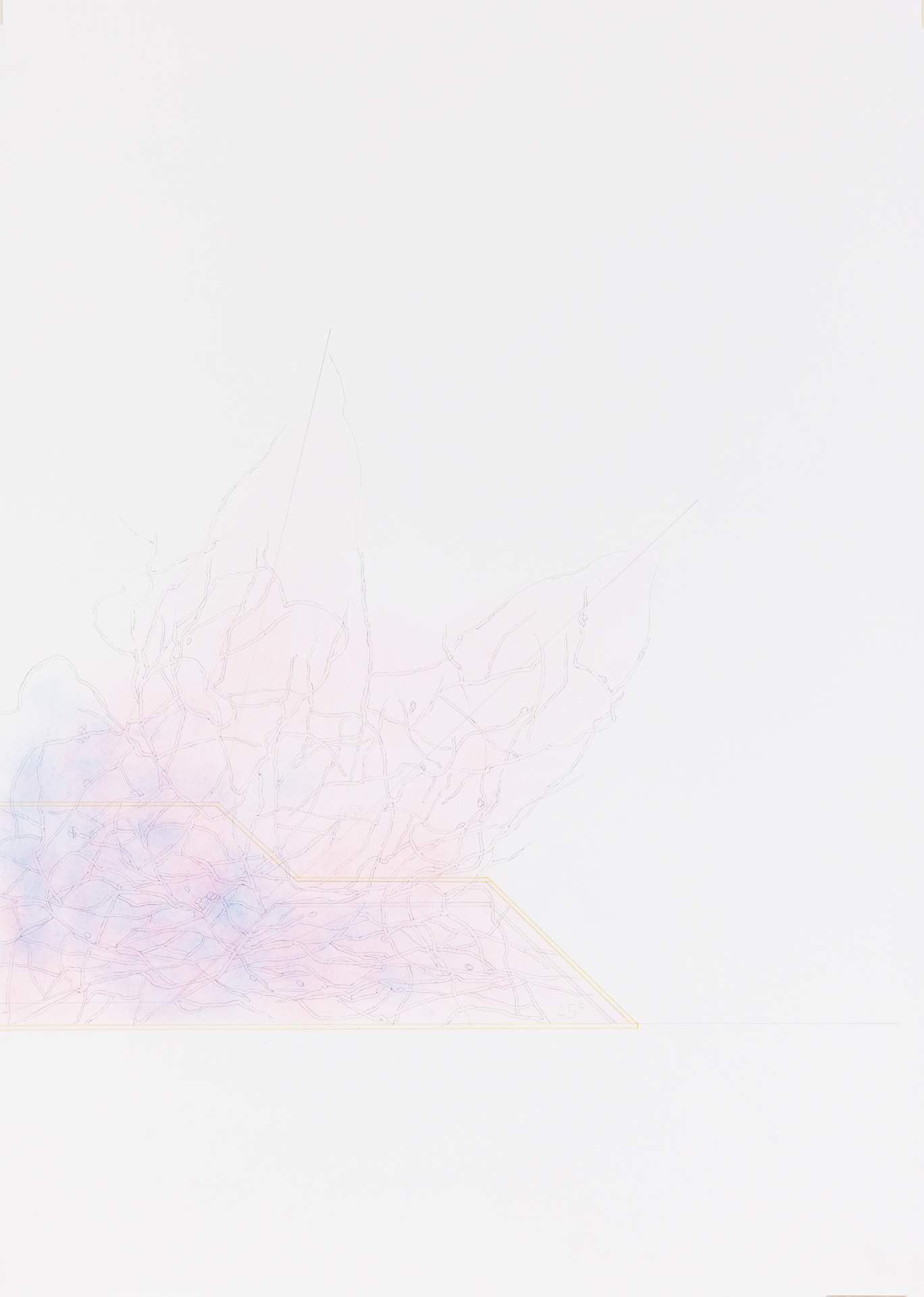

Infected Minds Will Heal The Future

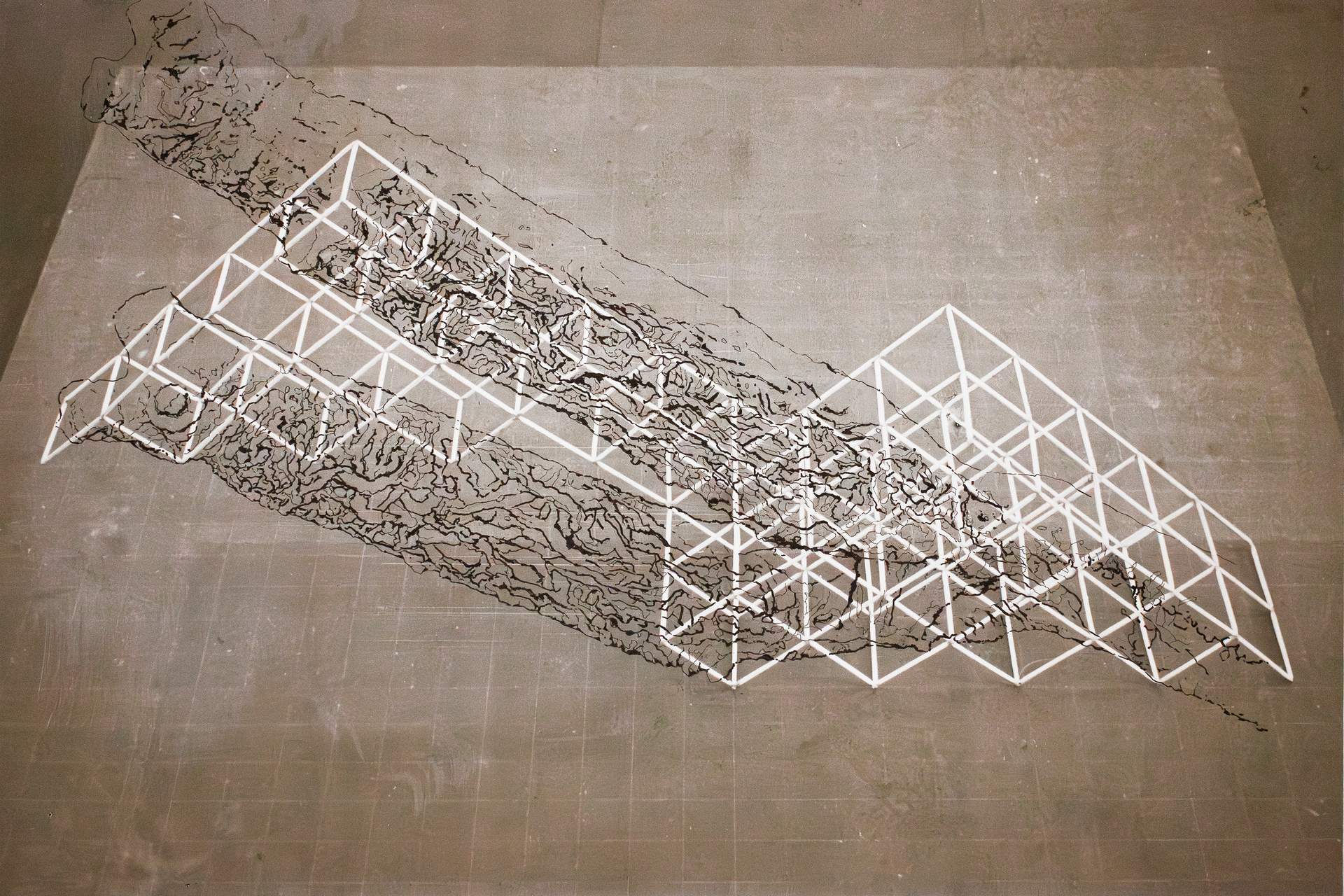

What would be if the built and the grown can't be distinguished anymore? This project is a speculative narrative exploring this idea. It envisions a world where building blocks are inspired by natural systems of ramification, utilizing fungal mycelium as a sustainable and ecological construction material. Ramification systems are an omnipresent growing mechanism in nature. The growth of mycelium is also based on that principle whereby computer generated branching is called "L-system". The animation showcases a dynamic matrix, where L-system blocks spontaneously assemble and self-organize into intricate structures. Inhale the spores to connect! "But how can I start to feel myself as not only human?" – Jane Bennett

Infected Minds Will Heal The Future

"Infected Minds Will Heal The Future" (2021) is a an ongoing speculative narrative, investigation and documentation about growth principles and fungal mycelium as an ecological material. How can we create together with the (living) environment instead of overusing its ressources? Is it possible to apply principles of the non-human to human lives by biomimicking them? The music for the video are recorded frequencies and fluctuations of a mycelium mushroom in real time. It was made by Aural. Shown at 15th edition of video club at Silent Green Berlin. Inhale the spores to connect!

FLAETTA

FLÄTTA is a versatile modular system crafted from mycelium blocks, designed to be easily and securely stacked through compression. The circular relief patterns on each block cast a soft interplay of shadows, creating a calming and inviting atmosphere. By combining individual blocks in various ways, up to six distinct patterns can be achieved, adding a unique aesthetic to any space. These mycelium blocks can be seamlessly integrated with oak wood shelving and glass modules, offering a flexible and functional room divider solution. The modular design allows for dividers that can reach either head height or full ceiling height, adapting perfectly to different room configurations. The only tool needed is a saw.

FLÄTTA

FLÄTTA is a versatile modular system crafted from mycelium blocks, designed to be easily and securely stacked through compression. The circular relief patterns on each block cast a soft interplay of shadows, creating a calming and inviting atmosphere. By combining individual blocks in various ways, up to six distinct patterns can be achieved, adding a unique aesthetic to any space. These mycelium blocks can be seamlessly integrated with oak wood shelving and glass modules, offering a flexible and functional room divider solution. The modular design allows for dividers that can reach either head height or full ceiling height, adapting perfectly to different room configurations. The only tool needed is a saw.

Toilet Paper Research

3D scan of dehydrated Pleurotus ostreatus grown on toilet paper “In the fertile depths of collective stupidity, a single grain of genius lies concealed, awaiting the transformative touch of insight.” At first, I panicked—not from the virus itself, but from the sheer absurdity of it all. Why toilet paper? Why were people acting like wiping their asses was the key to survival? I desperately tried to find a rational explanation—some hidden logic behind the madness. But then, a simple phone call with my mother gave me the answer I wasn’t expecting. Frustrated, I ranted about Germany’s pandemic policies, the toilet paper hoarding—and then I asked: “How are you guys doing?” (Living poor in Greece, during an economic crisis turned health crisis). She laughed bitterly and said: “Let’s just say that the only thing we can afford to eat is toilet paper.” That joke hit me like a punch to the gut. The split realities worldwide are unbearable—in some countries, people were hoarding disposable luxury, in other, people struggle to afford food, medicine, basic needs. I felt helpless. Angry. WTF are we doing on this planet? Stuck in a capitalist apocalypse with no way out. And then… my brain short-circuited into “How can I make toilet paper edible?” That frustration, that helplessness, turned into an idea: “A-ha! Growing mushrooms on toilet paper. Eating the mushrooms.” If capitalism gives us waste, let’s turn it into life.

Toilet Paper Research: Wiping Away Forests for the Illusion of Sanity

A Pandemic Tale of Hoarding and Absurdity March 2020. The world locked down. Streets emptied, fear spread, and suddenly, in privileged nations, supermarket shelves were stripped bare—not of food or medicine, but toilet paper. For those with running water, bidets, and soap, the obsession was irrational. Yet, panic-induced consumer behavior took over. While scientists worked on a vaccine, the masses stockpiled rolls like they were the last defense against collapse.

The Mycomancer

Xristina Sarlis' digital double with a 3D model of toilet paper and psilocybin mushrooms

Research Toilet Paper

“In the fertile depths of collective stupidity, a single grain of genius lies concealed, awaiting the transformative touch of insight.” At first, I panicked—not from the virus itself, but from the sheer absurdity of it all. Why toilet paper? Why were people acting like wiping their asses was the key to survival? I desperately tried to find a rational explanation—some hidden logic behind the madness. But then, a simple phone call with my mother gave me the answer I wasn’t expecting. Frustrated, I ranted about Germany’s pandemic policies, the toilet paper hoarding—and then I asked: “How are you guys doing?” (Living poor in Greece, during an economic crisis turned health crisis). She laughed bitterly and said: “Let’s just say that the only thing we can afford to eat is toilet paper.” That joke hit me like a punch to the gut. The split realities worldwide are unbearable—in some countries, people were hoarding disposable luxury, in other, people struggle to afford food, medicine, basic needs. I felt helpless. Angry. WTF are we doing on this planet? Stuck in a capitalist apocalypse with no way out. And then… my brain short-circuited into “How can I make toilet paper edible?” That frustration, that helplessness, turned into an idea: “A-ha! Growing mushrooms on toilet paper. Eating the mushrooms.” If capitalism gives us waste, let’s turn it into life.

In the Fertile Depths of Collective Stupidity

Pleurotus Ostreatus on Toilet Paper “In the fertile depths of collective stupidity, a single grain of genius lies concealed, awaiting the transformative touch of insight.” At first, I panicked—not from the virus itself, but from the sheer absurdity of it all. Why toilet paper? Why were people acting like wiping their asses was the key to survival? I desperately tried to find a rational explanation—some hidden logic behind the madness. But then, a simple phone call with my mother gave me the answer I wasn’t expecting. Frustrated, I ranted about Germany’s pandemic policies, the toilet paper hoarding—and then I asked: “How are you guys doing?” (Living poor in Greece, during an economic crisis turned health crisis). She laughed bitterly and said: “Let’s just say that the only thing we can afford to eat is toilet paper.” That joke hit me like a punch to the gut. The split realities worldwide are unbearable—in some countries, people were hoarding disposable luxury, in other, people struggle to afford food, medicine, basic needs. I felt helpless. Angry. WTF are we doing on this planet? Stuck in a capitalist apocalypse with no way out. And then… my brain short-circuited into “How can I make toilet paper edible?” That frustration, that helplessness, turned into an idea: “A-ha! Growing mushrooms on toilet paper. Eating the mushrooms.” If capitalism gives us waste, let’s turn it into life.

Toilet Paper Research

Pleurotus Ostreatus on Toilet Paper “In the fertile depths of collective stupidity, a single grain of genius lies concealed, awaiting the transformative touch of insight.” At first, I panicked—not from the virus itself, but from the sheer absurdity of it all. Why toilet paper? Why were people acting like wiping their asses was the key to survival? I desperately tried to find a rational explanation—some hidden logic behind the madness. But then, a simple phone call with my mother gave me the answer I wasn’t expecting. Frustrated, I ranted about Germany’s pandemic policies, the toilet paper hoarding—and then I asked: “How are you guys doing?” (Living poor in Greece, during an economic crisis turned health crisis). She laughed bitterly and said: “Let’s just say that the only thing we can afford to eat is toilet paper.” That joke hit me like a punch to the gut. The split realities worldwide are unbearable—in some countries, people were hoarding disposable luxury, in other, people struggle to afford food, medicine, basic needs. I felt helpless. Angry. WTF are we doing on this planet? Stuck in a capitalist apocalypse with no way out. And then… my brain short-circuited into “How can I make toilet paper edible?” That frustration, that helplessness, turned into an idea: “A-ha! Growing mushrooms on toilet paper. Eating the mushrooms.” If capitalism gives us waste, let’s turn it into life.

Toilet Paper Research

Pleurotus Ostreatus on Toilet Paper “In the fertile depths of collective stupidity, a single grain of genius lies concealed, awaiting the transformative touch of insight.” At first, I panicked—not from the virus itself, but from the sheer absurdity of it all. Why toilet paper? Why were people acting like wiping their asses was the key to survival? I desperately tried to find a rational explanation—some hidden logic behind the madness. But then, a simple phone call with my mother gave me the answer I wasn’t expecting. Frustrated, I ranted about Germany’s pandemic policies, the toilet paper hoarding—and then I asked: “How are you guys doing?” (Living poor in Greece, during an economic crisis turned health crisis). She laughed bitterly and said: “Let’s just say that the only thing we can afford to eat is toilet paper.” That joke hit me like a punch to the gut. The split realities worldwide are unbearable—in some countries, people were hoarding disposable luxury, in other, people struggle to afford food, medicine, basic needs. I felt helpless. Angry. WTF are we doing on this planet? Stuck in a capitalist apocalypse with no way out. And then… my brain short-circuited into “How can I make toilet paper edible?” That frustration, that helplessness, turned into an idea: “A-ha! Growing mushrooms on toilet paper. Eating the mushrooms.” If capitalism gives us waste, let’s turn it into life.

Toilet Paper Research

Pleurotus Ostreatus on Toilet Paper “In the fertile depths of collective stupidity, a single grain of genius lies concealed, awaiting the transformative touch of insight.” At first, I panicked—not from the virus itself, but from the sheer absurdity of it all. Why toilet paper? Why were people acting like wiping their asses was the key to survival? I desperately tried to find a rational explanation—some hidden logic behind the madness. But then, a simple phone call with my mother gave me the answer I wasn’t expecting. Frustrated, I ranted about Germany’s pandemic policies, the toilet paper hoarding—and then I asked: “How are you guys doing?” (Living poor in Greece, during an economic crisis turned health crisis). She laughed bitterly and said: “Let’s just say that the only thing we can afford to eat is toilet paper.” That joke hit me like a punch to the gut. The split realities worldwide are unbearable—in some countries, people were hoarding disposable luxury, in other, people struggle to afford food, medicine, basic needs. I felt helpless. Angry. WTF are we doing on this planet? Stuck in a capitalist apocalypse with no way out. And then… my brain short-circuited into “How can I make toilet paper edible?” That frustration, that helplessness, turned into an idea: “A-ha! Growing mushrooms on toilet paper. Eating the mushrooms.” If capitalism gives us waste, let’s turn it into life.

Bioglitch: Genome Access and Data Extraction

This video documents the initial stage of the Bioglitch process, where the complete genome of Pestalotiopsis microspora is accessed from the open database of the National Library of Medicine (Genome assembly ASM4141201v1). The dataset, publicly available yet costly to generate, serves as the foundation for the project’s feedback loop. The genomic code—extracted, purified, and sequenced through standard molecular techniques involving nucleus isolation, free water, and PCR amplification—becomes a digital script for translation. This bioinformatic material is later processed through custom coding software, where each nucleotide (adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine) is assigned a sonic frequency. The process marks the transition from genetic information to sound data—an act of mycohacking and decoding with mycelium that transforms biology into signal. Bio-Glitch is a feedback loop between organism, medium, and machine. We mycohacked the extracted genome of Pestalotiopsis microspora, a plastic-eating fungus, and sonified its DNA sequence into sound frequencies. Each nucleotide, adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine, was given a distinct sonic heritage, becoming a noise mantra of genetic information. The sonified genome was recorded to magnetic audio tape, generating analog glitches, and also fed into oscilloscopes to create live visualizations of the frequencies. These visuals were captured with a VHS camcorder and re-written over a found VHS tape of DIY skate recordings, collapsing biological data and cultural residue into the same signal. The altered VHS tapes were then returned as a feedback offering to Pestalotiopsis microspora, incubated on malt agar at 25 °C. As the fungus consumes polyurethane binders in the tape, it decomposes the very object that now contains its own genomic sound. The result is a recursive circuit: data extracted from the organism returns as both sonic and material food for the organism itself. This project turns pollution into art. Plastic, noise, and analog media become spaces for collaboration, blending old knowledge with technology. Using fungi to break down waste, it explores the blurred lines between life, matter, and data. It imagines futures without plastic, where the fungus helps free us from the cycle of pollution. A multispecies ritual to transform plastic-infected dreams. This project is presented through various artistic forms and is an ongoing experiment in mycohacking the future, created in collaboration with Alexandra Maciá, Giorgio Alloatti, and Xristina Sarli.

Bioglitch I (DNA Conversion Protocol): Genome to Polyurethane Tape Recording

This video documents the feedback process where biological data becomes sound and image. The extracted genome of Pestalotiopsis microspora—a plastic-degrading fungus—is translated from nucleotide code (adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine) into corresponding sound frequencies. Through custom software, the genome’s timing and rhythm are rendered into sonic pulses, recorded in real time onto polyurethane-based magnetic tape. The same digital sonification feeds into an oscilloscope, generating a live waveform visualization of the fungal DNA’s vibrational pattern. This recursive circuit between organism, medium, and machine materializes data as both analog noise and electromagnetic image—a living signal inscribed in multiple formats. Bio-Glitch is a feedback loop between organism, medium, and machine. We mycohacked the extracted genome of Pestalotiopsis microspora, a plastic-eating fungus, and sonified its DNA sequence into sound frequencies. Each nucleotide, adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine, was given a distinct sonic heritage, becoming a noise mantra of genetic information. The sonified genome was recorded to magnetic audio tape, generating analog glitches, and also fed into oscilloscopes to create live visualizations of the frequencies. These visuals were captured with a VHS camcorder and re-written over a found VHS tape of DIY skate recordings, collapsing biological data and cultural residue into the same signal. The altered VHS tapes were then returned as a feedback offering to Pestalotiopsis microspora, incubated on malt agar at 25 °C. As the fungus consumes polyurethane binders in the tape, it decomposes the very object that now contains its own genomic sound. The result is a recursive circuit: data extracted from the organism returns as both sonic and material food for the organism itself. This project turns pollution into art. Plastic, noise, and analog media become spaces for collaboration, blending old knowledge with technology. Using fungi to break down waste, it explores the blurred lines between life, matter, and data. It imagines futures without plastic, where the fungus helps free us from the cycle of pollution. A multispecies ritual to transform plastic-infected dreams. This project is presented through various artistic forms and is an ongoing experiment in mycohacking the future, created in collaboration with Alexandra Maciá, Giorgio Alloatti, and Xristina Sarli.

Bioglitch II: Genome Oscilation (Oscilloscope Screen)

This screen displays the live oscillation of a sonified DNA sequence from Pestalotiopsis microspora, a plastic-degrading fungus. The genetic code—translated from adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine into sonic frequencies—forms an audiovisual feedback loop between organism and machine. The waveform becomes a living signal: biological data rendered as sound, then visualized through electronic circuitry. The glowing undulation is both code and chant, an electromagnetic echo of genetic rhythm captured in real time. Bio-Glitch is a feedback loop between organism, medium, and machine. We mycohacked the extracted genome of Pestalotiopsis microspora, a plastic-eating fungus, and sonified its DNA sequence into sound frequencies. Each nucleotide, adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine, was given a distinct sonic heritage, becoming a noise mantra of genetic information. The sonified genome was recorded to magnetic audio tape, generating analog glitches, and also fed into oscilloscopes to create live visualizations of the frequencies. These visuals were captured with a VHS camcorder and re-written over a found VHS tape of DIY skate recordings, collapsing biological data and cultural residue into the same signal. The altered VHS tapes were then returned as a feedback offering to Pestalotiopsis microspora, incubated on malt agar at 25 °C. As the fungus consumes polyurethane binders in the tape, it decomposes the very object that now contains its own genomic sound. The result is a recursive circuit: data extracted from the organism returns as both sonic and material food for the organism itself. This project turns pollution into art. Plastic, noise, and analog media become spaces for collaboration, blending old knowledge with technology. Using fungi to break down waste, it explores the blurred lines between life, matter, and data. It imagines futures without plastic, where the fungus helps free us from the cycle of pollution. A multispecies ritual to transform plastic-infected dreams. This project is presented through various artistic forms and is an ongoing experiment in mycohacking the future, created in collaboration with Alexandra Maciá, Giorgio Alloatti, and Xristina Sarli.

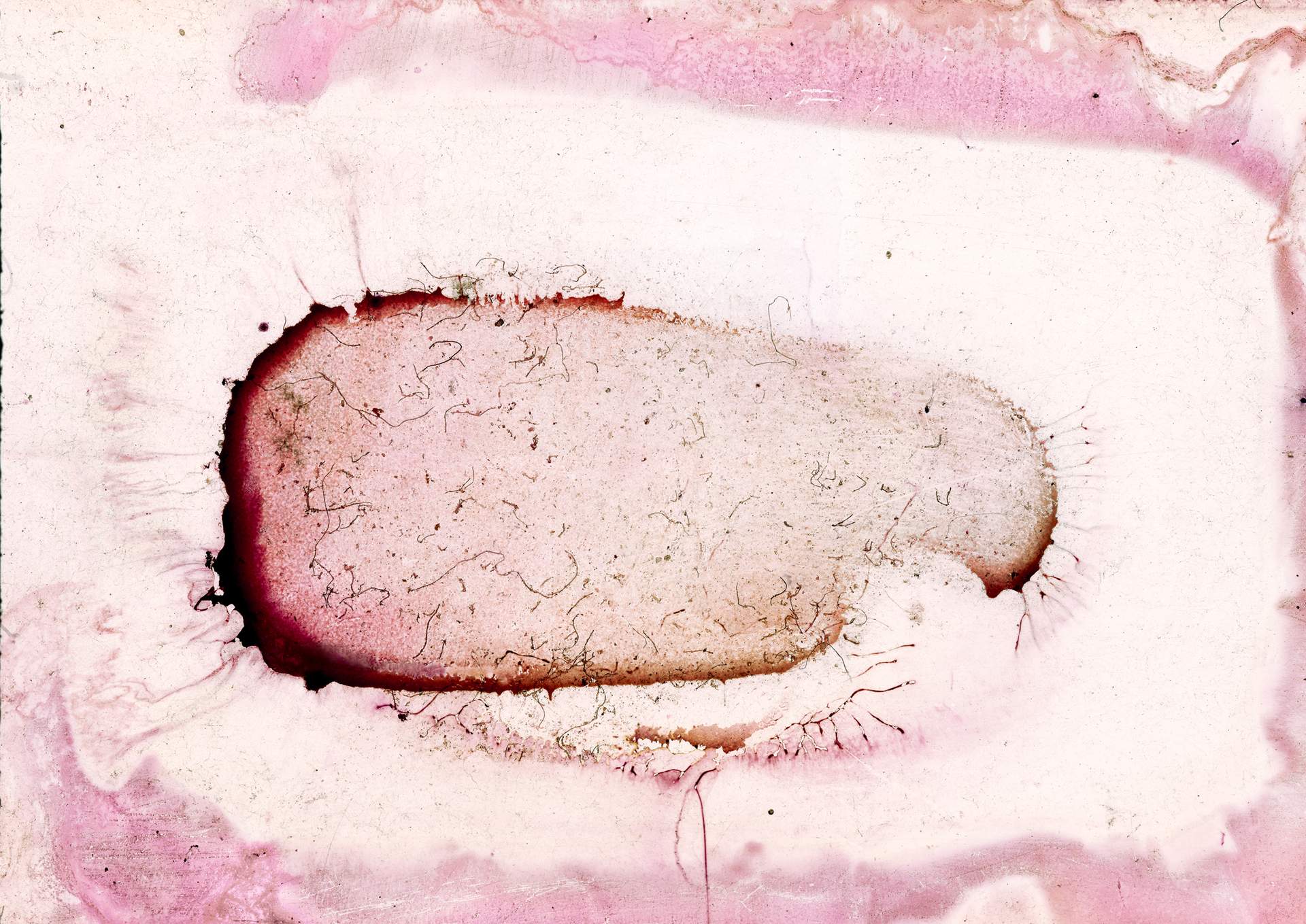

Bioglitch III: Feedback Offering (Magnetic Tape Incubation)

In this stage of Bioglitch, the sonified and magnetically recorded DNA of Pestalotiopsis microspora is returned to its own biological substrate. Segments of the polyurethane-based audio tapes—each containing a 30-second sequence of the fungus’s translated genome—are plated onto malt-agar culture media where Pestalotiopsis continues to grow. This gesture closes the feedback circuit: the organism receives back its own signal, now transformed through layers of data, sound, and material inscription. The magnetic tape, a synthetic polymer akin to plastic waste, becomes both medium and host—a site of bioelectronic communion where cultural residue meets living matter. Bio-Glitch is a feedback loop between organism, medium, and machine. We mycohacked the extracted genome of Pestalotiopsis microspora, a plastic-eating fungus, and sonified its DNA sequence into sound frequencies. Each nucleotide, adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine, was given a distinct sonic heritage, becoming a noise mantra of genetic information. The sonified genome was recorded to magnetic audio tape, generating analog glitches, and also fed into oscilloscopes to create live visualizations of the frequencies. These visuals were captured with a VHS camcorder and re-written over a found VHS tape of DIY skate recordings, collapsing biological data and cultural residue into the same signal. The altered VHS tapes were then returned as a feedback offering to Pestalotiopsis microspora, incubated on malt agar at 25 °C. As the fungus consumes polyurethane binders in the tape, it decomposes the very object that now contains its own genomic sound. The result is a recursive circuit: data extracted from the organism returns as both sonic and material food for the organism itself. This project turns pollution into art. Plastic, noise, and analog media become spaces for collaboration, blending old knowledge with technology. Using fungi to break down waste, it explores the blurred lines between life, matter, and data. It imagines futures without plastic, where the fungus helps free us from the cycle of pollution. A multispecies ritual to transform plastic-infected dreams. This project is presented through various artistic forms and is an ongoing experiment in mycohacking the future, created in collaboration with Alexandra Maciá, Giorgio Alloatti, and Xristina Sarli.

Bioglitch IV: VHS Feedback Recording

This video documents the stage where the biosonified DNA of Pestalotiopsis microspora—visualized through an oscilloscope—is recorded using a VHS camera directly onto magnetic VHS tape. The analog setup combines oscilloscope, VHS recorder, and monitor to create a feedback circuit where digital, electronic, and biological data converge. The VHS tape, composed of polyurethane, shares a chemical kinship with the plastics the fungus can degrade. After recording, the altered tapes are plated onto Pestalotiopsis cultures, allowing the organism to physically interact with its own sonified and visualized genome inscribed on polymeric film. This act transforms the medium into both signal carrier and biological offering, collapsing distinctions between information, material, and organism. Bio-Glitch is a feedback loop between organism, medium, and machine. We mycohacked the extracted genome of Pestalotiopsis microspora, a plastic-eating fungus, and sonified its DNA sequence into sound frequencies. Each nucleotide, adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine, was given a distinct sonic heritage, becoming a noise mantra of genetic information. The sonified genome was recorded to magnetic audio tape, generating analog glitches, and also fed into oscilloscopes to create live visualizations of the frequencies. These visuals were captured with a VHS camcorder and re-written over a found VHS tape of DIY skate recordings, collapsing biological data and cultural residue into the same signal. The altered VHS tapes were then returned as a feedback offering to Pestalotiopsis microspora, incubated on malt agar at 25 °C. As the fungus consumes polyurethane binders in the tape, it decomposes the very object that now contains its own genomic sound. The result is a recursive circuit: data extracted from the organism returns as both sonic and material food for the organism itself. This project turns pollution into art. Plastic, noise, and analog media become spaces for collaboration, blending old knowledge with technology. Using fungi to break down waste, it explores the blurred lines between life, matter, and data. It imagines futures without plastic, where the fungus helps free us from the cycle of pollution. A multispecies ritual to transform plastic-infected dreams. This project is presented through various artistic forms and is an ongoing experiment in mycohacking the future, created in collaboration with Alexandra Maciá, Giorgio Alloatti, and Xristina Sarli.

Recording the Sonified Genome on Polyurethane VHS Tape

This video documents the stage where the biosonified DNA of Pestalotiopsis microspora—visualized through an oscilloscope—is recorded using a VHS camera directly onto magnetic VHS tape. The analog setup combines oscilloscope, VHS recorder, and monitor to create a feedback circuit where digital, electronic, and biological data converge. The VHS tape, composed of polyurethane, shares a chemical kinship with the plastics the fungus can degrade. After recording, the altered tapes are plated onto Pestalotiopsis cultures, allowing the organism to physically interact with its own sonified and visualized genome inscribed on polymeric film. This act transforms the medium into both signal carrier and biological offering, collapsing distinctions between information, material, and organism.

Pestalotiopsis Microspora on VHS polyurethane tape (Mycelium Interfacing with Recorded Genome)

In this image, Pestalotiopsis microspora mycelium is seen colonizing the surface of polyurethane-based magnetic tape containing its own sonified genetic sequence. The organism interacts with the very polymer it can metabolize, engaging in a feedback act where biological data and material substrate converge. The tape, once a carrier of analog sound and visual signal, becomes a living interface—an ecological and technological medium simultaneously. Through this gesture, the Bioglitch cycle reaches completion: the fungus reclaims its digitized essence, inscribed in noise and plastic, translating information back into organic form.

-n9FAV6Qu.jpg)

Feedback Setup Scan (Alexandra Maciá´s Studio)

INSIDE THE JELLY BASIN

INSIDE THE JELLY BASIN

INSIDE THE JELLY BASIN

INSIDE THE JELLY BASIN

Weaving a Rhizome Performance

INSIDE THE JELLY BASIN

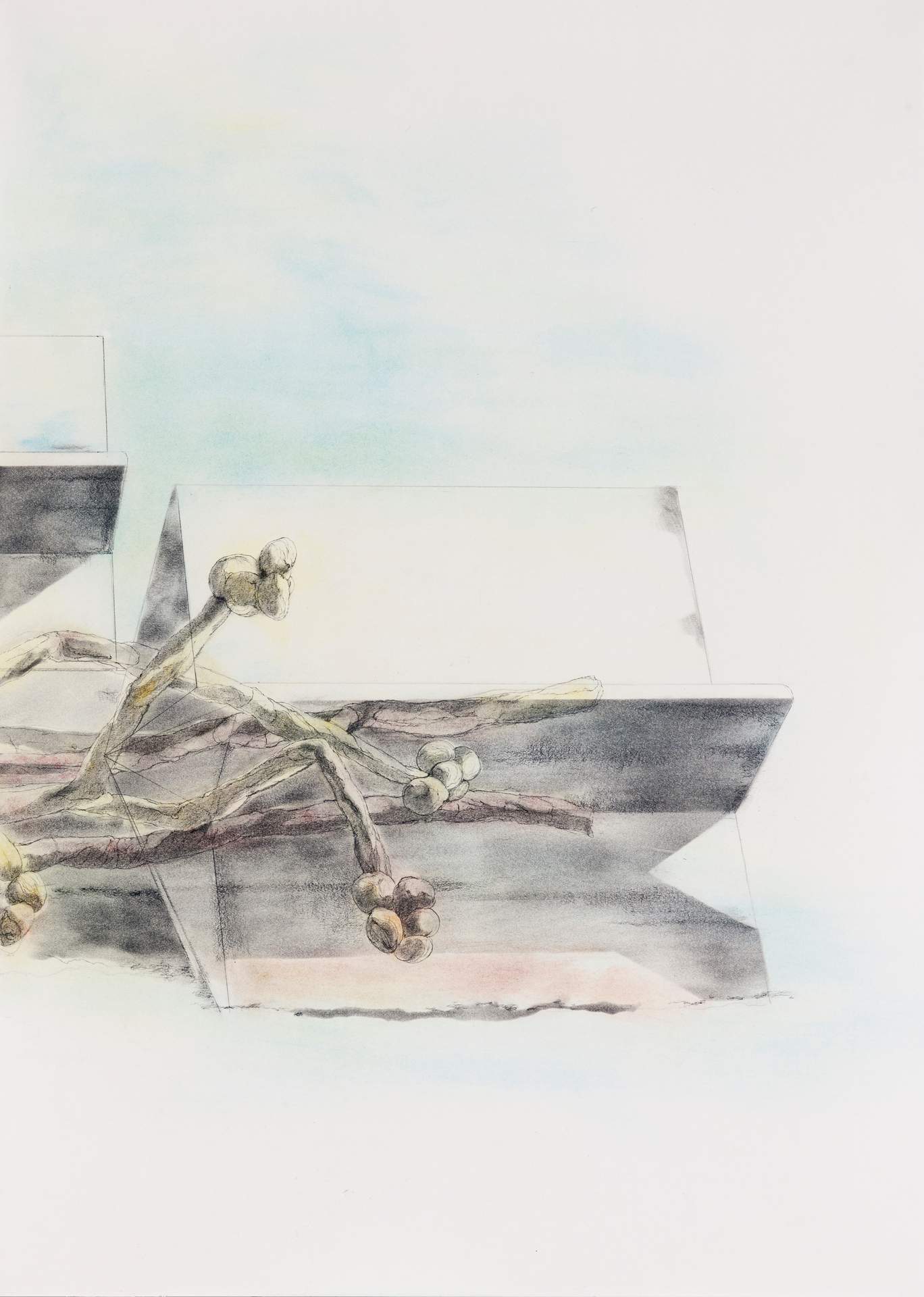

FUNGALphonic Records sculptures I hemp & mycelium prototypes I 10'' various sizes, 2024

Fungalphonic records are mycelium-grown discs that undergo processes of de-composition and re-composition. They are an invitation for fungal microstructures to explore and resculpt the topographical grooves of record discs. In the face of climate change and collapsing ecosystems, the project directs its focus to alternative biomaterials for media objects instead of the established preshaped and passive materials of extractivist practices. Rather than spreading through cracks in wood, the mycelium with its thread-like cells of hyphae follows the engravings of sound waves on a record. The wood-rotting fungus Fomes fomentarius thereby imprints itself into disc form – leaving behind patterns of its rhizomorphic journey as a travel memory. The fungus also grows its own velvet-like skin which covers and overwrites existing grooves. The particular textures of the newly shaped disc present specific fungal surfaces to be rendered into sonic events on a record player. Making and growing shape both sculptural and sonic attributes.

Wax & Wane

Beeswax records, turntables, 2023 Wax & Wane explores the sculptural and sonic link between local culture and urban nature by using custom-made records from regional beeswax. Karin Weissenbrunner and JD Zazie’s duo project unites the honeybees’ ›voices‹ as equal co-creators with their own wax, while recycling recordings of Berlin’s sound archives through the wax material. The key focus is to fully embrace the organic material with varying qualities in color, smell, or consistency specific to its origin environment – and to render these material features into a sonic experience. For these unique records, the sound artists collaborated mainly with city beekeepers from the Mellifera society, who keep honeybees ‘organically’ on rooftops or in gardens and cemeteries, and Berlin related sound archives, such as the Lautarchiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, the Tierstimmenarchiv of Museum für Naturkunde and radio aporee. The project aims to situate turntable practices in the current context of environmental concerns and, in particular, to draw attention to the decline of insect populations – one of the less noticeable consequences of human intervention in natural systems. Rather than spreading through cracks in wood, the mycelium with its thread-like cells of hyphae follows the engravings of sound waves on a record. The wood-rotting fungus Fomes fomentarius thereby imprints itself into disc form – leaving behind patterns of its rhizomorphic journey as a travel memory. The fungus also grows its own velvet-like skin which covers and overwrites existing grooves. The particular textures of the newly shaped disc present specific fungal surfaces to be rendered into sonic events on a record player. Making and growing shape both sculptural and sonic attributes.

Wax & Wane

Beeswax records, turntables, 2023 Wax & Wane explores the sculptural and sonic link between local culture and urban nature by using custom-made records from regional beeswax. Karin Weissenbrunner and JD Zazie’s duo project unites the honeybees’ ›voices‹ as equal co-creators with their own wax, while recycling recordings of Berlin’s sound archives through the wax material. The key focus is to fully embrace the organic material with varying qualities in color, smell, or consistency specific to its origin environment – and to render these material features into a sonic experience. For these unique records, the sound artists collaborated mainly with city beekeepers from the Mellifera society, who keep honeybees ‘organically’ on rooftops or in gardens and cemeteries, and Berlin related sound archives, such as the Lautarchiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, the Tierstimmenarchiv of Museum für Naturkunde and radio aporee. The project aims to situate turntable practices in the current context of environmental concerns and, in particular, to draw attention to the decline of insect populations – one of the less noticeable consequences of human intervention in natural systems. Rather than spreading through cracks in wood, the mycelium with its thread-like cells of hyphae follows the engravings of sound waves on a record. The wood-rotting fungus Fomes fomentarius thereby imprints itself into disc form – leaving behind patterns of its rhizomorphic journey as a travel memory. The fungus also grows its own velvet-like skin which covers and overwrites existing grooves. The particular textures of the newly shaped disc present specific fungal surfaces to be rendered into sonic events on a record player. Making and growing shape both sculptural and sonic attributes.

FUNGALphonic Records sculptures I hemp & mycelium prototypes I 10'' various sizes, 2024

Fungalphonic records are mycelium-grown discs that undergo processes of de-composition and re-composition. They are an invitation for fungal microstructures to explore and resculpt the topographical grooves of record discs. In the face of climate change and collapsing ecosystems, the project directs its focus to alternative biomaterials for media objects instead of the established preshaped and passive materials of extractivist practices. Rather than spreading through cracks in wood, the mycelium with its thread-like cells of hyphae follows the engravings of sound waves on a record. The wood-rotting fungus Fomes fomentarius thereby imprints itself into disc form – leaving behind patterns of its rhizomorphic journey as a travel memory. The fungus also grows its own velvet-like skin which covers and overwrites existing grooves. The particular textures of the newly shaped disc present specific fungal surfaces to be rendered into sonic events on a record player. Making and growing shape both sculptural and sonic attributes. Rather than spreading through cracks in wood, the mycelium with its thread-like cells of hyphae follows the engravings of sound waves on a record. The wood-rotting fungus Fomes fomentarius thereby imprints itself into disc form – leaving behind patterns of its rhizomorphic journey as a travel memory. The fungus also grows its own velvet-like skin which covers and overwrites existing grooves. The particular textures of the newly shaped disc present specific fungal surfaces to be rendered into sonic events on a record player. Making and growing shape both sculptural and sonic attributes. Rather than spreading through cracks in wood, the mycelium with its thread-like cells of hyphae follows the engravings of sound waves on a record. The wood-rotting fungus Fomes fomentarius thereby imprints itself into disc form – leaving behind patterns of its rhizomorphic journey as a travel memory. The fungus also grows its own velvet-like skin which covers and overwrites existing grooves. The particular textures of the newly shaped disc present specific fungal surfaces to be rendered into sonic events on a record player. Making and growing shape both sculptural and sonic attributes.

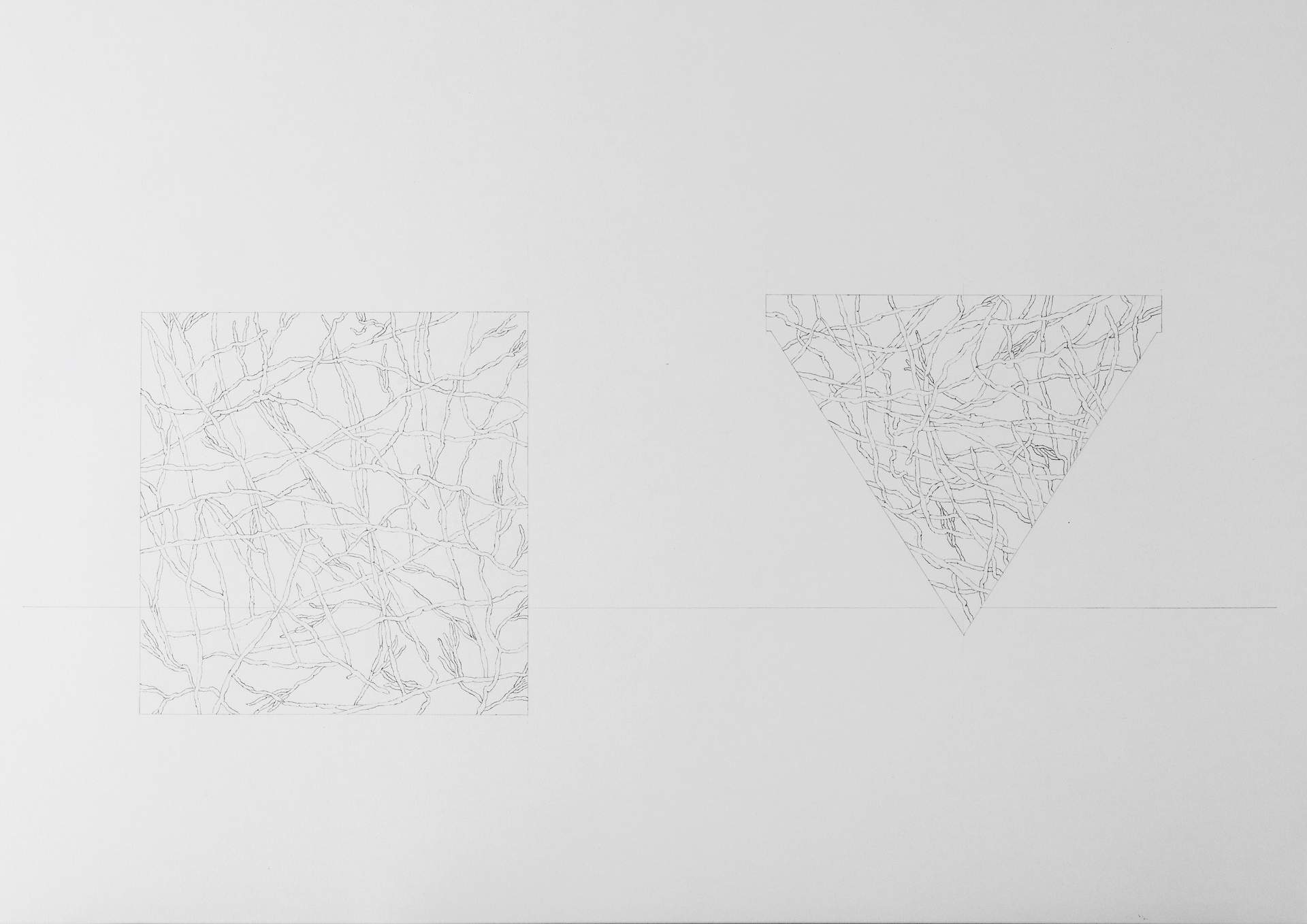

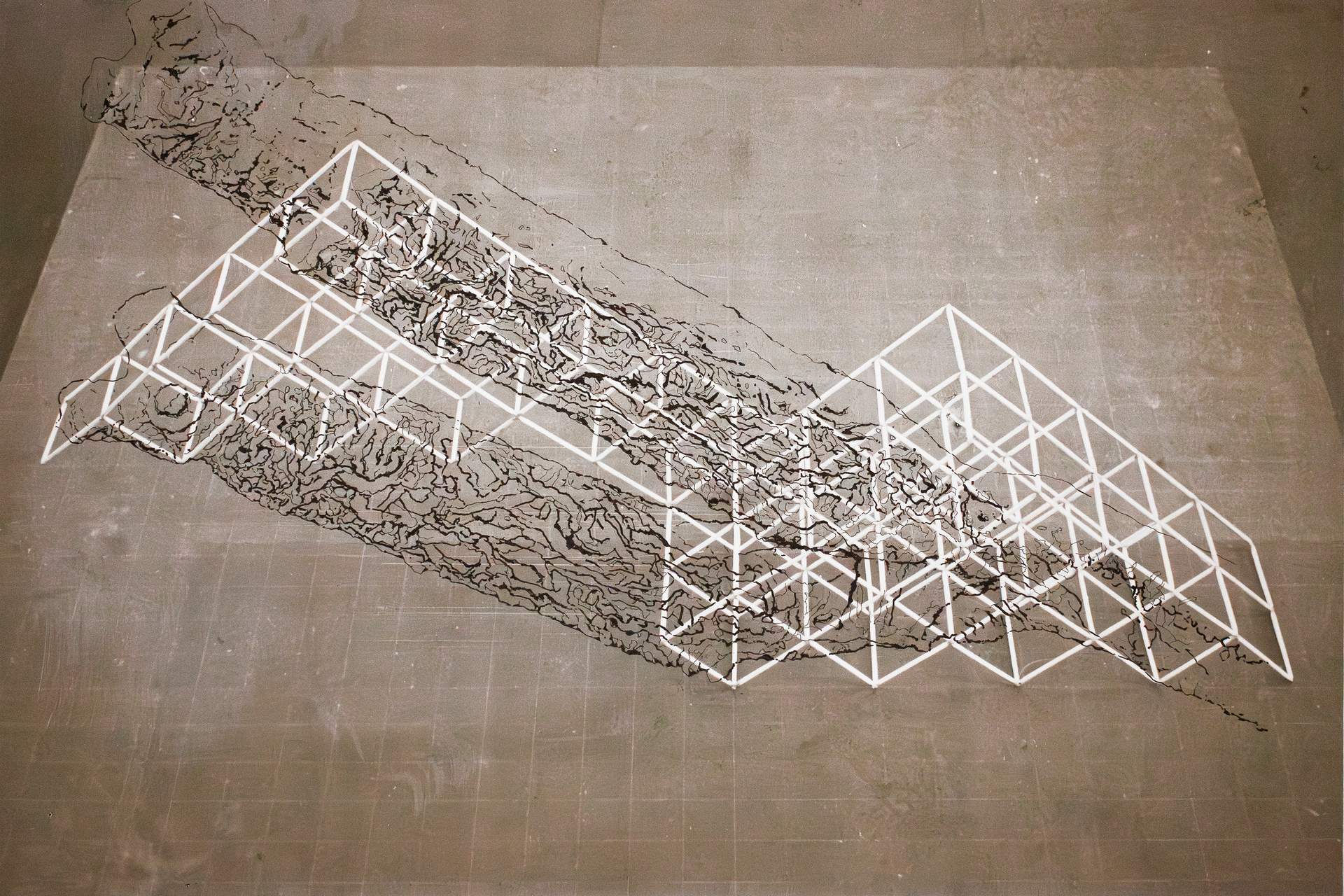

FUNGALphonic Records sculptures I hemp & mycelium prototypes I 10'' various sizes, 2024

3D scanned prototypes. Fungalphonic records are mycelium-grown discs that undergo processes of de-composition and re-composition. They are an invitation for fungal microstructures to explore and resculpt the topographical grooves of record discs. In the face of climate change and collapsing ecosystems, the project directs its focus to alternative biomaterials for media objects instead of the established preshaped and passive materials of extractivist practices. Rather than spreading through cracks in wood, the mycelium with its thread-like cells of hyphae follows the engravings of sound waves on a record. The wood-rotting fungus Fomes fomentarius thereby imprints itself into disc form – leaving behind patterns of its rhizomorphic journey as a travel memory. The fungus also grows its own velvet-like skin which covers and overwrites existing grooves. The particular textures of the newly shaped disc present specific fungal surfaces to be rendered into sonic events on a record player. Making and growing shape both sculptural and sonic attributes. Rather than spreading through cracks in wood, the mycelium with its thread-like cells of hyphae follows the engravings of sound waves on a record. The wood-rotting fungus Fomes fomentarius thereby imprints itself into disc form – leaving behind patterns of its rhizomorphic journey as a travel memory. The fungus also grows its own velvet-like skin which covers and overwrites existing grooves. The particular textures of the newly shaped disc present specific fungal surfaces to be rendered into sonic events on a record player. Making and growing shape both sculptural and sonic attributes.

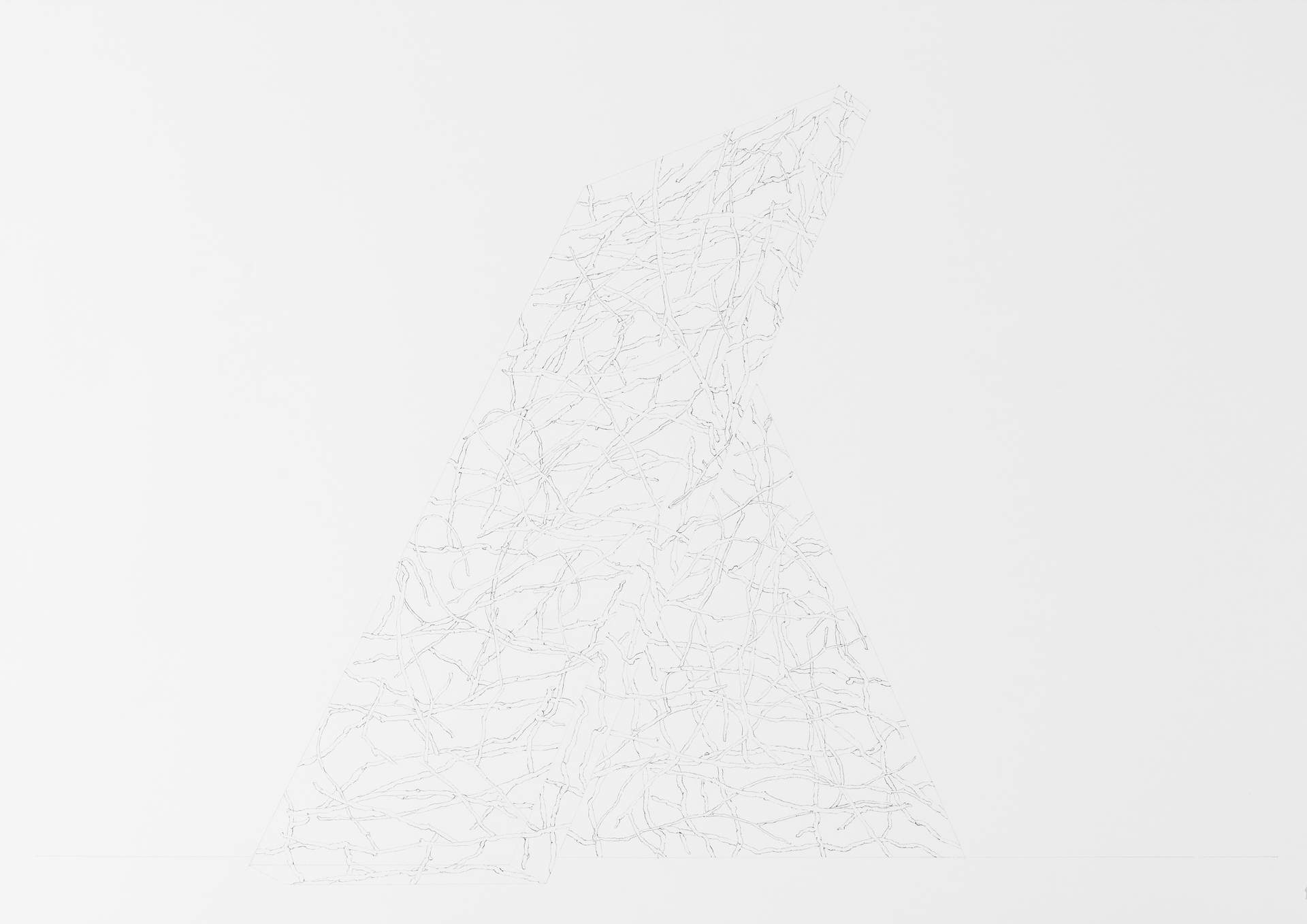

FUNGALphonic Records sculptures I hemp & mycelium prototypes I 10'' various sizes, 2024

3D scanned prototypes. Fungalphonic records are mycelium-grown discs that undergo in processes of de-composition and re-composition. They are an invitation for fungal microstructures to explore and resculpt the topographical grooves of record discs. In the face of climate change and collapsing ecosystems, the project directs its focus to alternative biomaterials for media objects instead of the established preshaped and passive materials of extractivist practices. Rather than spreading through cracks in wood, the mycelium with its thread-like cells of hyphae follows the engravings of sound waves on a record. The wood-rotting fungus Fomes fomentarius thereby imprints itself into disc form – leaving behind patterns of its rhizomorphic journey as a travel memory. The fungus also grows its own velvet-like skin which covers and overwrites existing grooves. The particular textures of the newly shaped disc present specific fungal surfaces to be rendered into sonic events on a record player. Making and growing shape both sculptural and sonic attributes.

EXIT marks the Spot

3D scan, Cotton and silk thread on mycelium based leather, 2025 I look at in flight safety instructions for a shared iconography of disaster, and for the ritual of forseeing it, conjuring it, and endlessly rehearsing it. The muted colors and timeless visual grammar brush against catastrophe all the while pitching salvation by means of attentive preparation. The promise soothes and unsettles, inevitably bringing into question all skills and tools. I set myself up to contemplate and repeat the icons. I imagine bringing the gap between the mass printed human figures and myself. I try to think of future tripping into an almost meditative practice, one that is collective and intimate at the same time. ANNA MADDALENA CINGI is a designer, artist and tinkerer with roots in Reggio Emilia (Italy). She studied set, costume and puppet design at Brera Academy of Fine Arts and at Accademia Teatro alla Scala. Since then, she has been working nomadically for theatres everywhere, such as Wiener Volkstheater, Stadttheater Gießen, Artisti Associati Gorizia, Teatro Franco Parenti, Biennale Teatro di Venezia, CTM festival, PACT Zollverein, Teatro Alla Scala, Wiener Volksoper, Latvian National Opera, Oper am Rhein, and more. In 2019 she was awarded the Premio Tragos as up-and-coming set designer for Visite (I Gordi/Teatro Franco Parenti). Her active collaborations include I Gordi, ArtesMobiles, and designers Julian Crouch and Christof Hetzer.

Cordyceps Tarantula 01

3D artwork (photogrammetry and modeling)

Cordyceps Tarantula 02

3D artwork (photogrammetry and modeling) Researchers think the fungus, found in tropical forests, infects a foraging ant through spores that attach and penetrate the exoskeleton and slowly takes over its behavior.

12 legs. 10 wings. The Damselkaupi 4x2ii - hovers upside down in perfect stasis.

Spider body with extra legs - Thailand black tarantula - Mygale : Cyriopagopus minax Wings -Damselfly -Neurobasis Kaupi -Indonesia 12 legs. 10 wings. The Damselkaupi 4x2ii - hovers upside down in perfect stasis. Height: 50mm Weight: 24g Distant universe or a distant future? A minute tweak in Earth’s living conditions could cause evolutionary chaos. These specimens are indeed all made from real insects from the real planet we live on. But we imagine how they might have formed in places where the gravitational pull was 9.5 metres per second squared, not 9.8. Oxygen at 19%, not 21%, and the temperature just a few degrees higher or lower on average. Perhaps they were sent to us by an alien race, in tiny little rockets as tiny little gifts. So cute. Perhaps they were sent at us in tiny little rockets, as tiny little parasites. Death by pincer, death by poison. Maybe they are from our planet but they were sent back in time. Maybe they found their own way back. Futuristic lifeform that now rules the Earth in the year 322025. Neo-insect time travel using venom webs. Maybe they are from the pre-historic past, slowly burrowing their way through the earth’s crust over the last 250 million years. The heat preserving their bodies as they almost starve on a diet of hydrocarbons and radioactive minerals. Alfie Greenwood, born in the Forest of Dean in England, moved to Berlin at the start of 2024. His artwork explores the alchemy of taxidermy and imagination by merging parts from different insects to create mutant creatures. These hybrids balance between chaotic organic forms and mythical deviations in evolution, embodying a surreal distortion of natural life. Alfie presents these mutant insects in encased quadrangular structures crafted from resin, plastic, and various organic materials, creating a striking contrast between wild mutation and geometric order. His work navigates the tension between nature’s unpredictability and human attempts to frame and contain it, inviting viewers to confront the fragile boundary between reality and fantasy.

12 legs. 10 wings. The Damselkaupi 4x2ii - hovers upside down in perfect stasis.

Spider body with extra legs - Thailand black tarantula - Mygale : Cyriopagopus minax Wings -Damselfly -Neurobasis Kaupi -Indonesia 12 legs. 10 wings. The Damselkaupi 4x2ii - hovers upside down in perfect stasis. Height: 50mm Weight: 24g Distant universe or a distant future? A minute tweak in Earth’s living conditions could cause evolutionary chaos. These specimens are indeed all made from real insects from the real planet we live on. But we imagine how they might have formed in places where the gravitational pull was 9.5 metres per second squared, not 9.8. Oxygen at 19%, not 21%, and the temperature just a few degrees higher or lower on average. Perhaps they were sent to us by an alien race, in tiny little rockets as tiny little gifts. So cute. Perhaps they were sent at us in tiny little rockets, as tiny little parasites. Death by pincer, death by poison. Maybe they are from our planet but they were sent back in time. Maybe they found their own way back. Futuristic lifeform that now rules the Earth in the year 322025. Neo-insect time travel using venom webs. Maybe they are from the pre-historic past, slowly burrowing their way through the earth’s crust over the last 250 million years. The heat preserving their bodies as they almost starve on a diet of hydrocarbons and radioactive minerals. Alfie Greenwood, born in the Forest of Dean in England, moved to Berlin at the start of 2024. His artwork explores the alchemy of taxidermy and imagination by merging parts from different insects to create mutant creatures. These hybrids balance between chaotic organic forms and mythical deviations in evolution, embodying a surreal distortion of natural life. Alfie presents these mutant insects in encased quadrangular structures crafted from resin, plastic, and various organic materials, creating a striking contrast between wild mutation and geometric order. His work navigates the tension between nature’s unpredictability and human attempts to frame and contain it, inviting viewers to confront the fragile boundary between reality and fantasy.

12 legs. 10 wings. The Damselkaupi 4x2ii - hovers upside down in perfect stasis.

Spider body with extra legs - Thailand black tarantula - Mygale : Cyriopagopus minax Wings -Damselfly -Neurobasis Kaupi -Indonesia 12 legs. 10 wings. The Damselkaupi 4x2ii - hovers upside down in perfect stasis. Height: 50mm Weight: 24g Distant universe or a distant future? A minute tweak in Earth’s living conditions could cause evolutionary chaos. These specimens are indeed all made from real insects from the real planet we live on. But we imagine how they might have formed in places where the gravitational pull was 9.5 metres per second squared, not 9.8. Oxygen at 19%, not 21%, and the temperature just a few degrees higher or lower on average. Perhaps they were sent to us by an alien race, in tiny little rockets as tiny little gifts. So cute. Perhaps they were sent at us in tiny little rockets, as tiny little parasites. Death by pincer, death by poison. Maybe they are from our planet but they were sent back in time. Maybe they found their own way back. Futuristic lifeform that now rules the Earth in the year 322025. Neo-insect time travel using venom webs. Maybe they are from the pre-historic past, slowly burrowing their way through the earth’s crust over the last 250 million years. The heat preserving their bodies as they almost starve on a diet of hydrocarbons and radioactive minerals. Alfie Greenwood, born in the Forest of Dean in England, moved to Berlin at the start of 2024. His artwork explores the alchemy of taxidermy and imagination by merging parts from different insects to create mutant creatures. These hybrids balance between chaotic organic forms and mythical deviations in evolution, embodying a surreal distortion of natural life. Alfie presents these mutant insects in encased quadrangular structures crafted from resin, plastic, and various organic materials, creating a striking contrast between wild mutation and geometric order. His work navigates the tension between nature’s unpredictability and human attempts to frame and contain it, inviting viewers to confront the fragile boundary between reality and fantasy.

Wave scarab skimmer, tailed whip spinner

Body -Red arab beetle -Torynorrhina flammea -Malaysia Wave scarab skimmer, tailed whip spinner. Height: 10mm Weight: 13g Distant universe or a distant future? A minute tweak in Earth’s living conditions could cause evolutionary chaos. These specimens are indeed all made from real insects from the real planet we live on. But we imagine how they might have formed in places where the gravitational pull was 9.5 metres per second squared, not 9.8. Oxygen at 19%, not 21%, and the temperature just a few degrees higher or lower on average. Perhaps they were sent to us by an alien race, in tiny little rockets as tiny little gifts. So cute. Perhaps they were sent at us in tiny little rockets, as tiny little parasites. Death by pincer, death by poison. Maybe they are from our planet but they were sent back in time. Maybe they found their own way back. Futuristic lifeform that now rules the Earth in the year 322025. Neo-insect time travel using venom webs. Maybe they are from the pre-historic past, slowly burrowing their way through the earth’s crust over the last 250 million years. The heat preserving their bodies as they almost starve on a diet of hydrocarbons and radioactive minerals. Alfie Greenwood, born in the Forest of Dean in England, moved to Berlin at the start of 2024. His artwork explores the alchemy of taxidermy and imagination by merging parts from different insects to create mutant creatures. These hybrids balance between chaotic organic forms and mythical deviations in evolution, embodying a surreal distortion of natural life. Alfie presents these mutant insects in encased quadrangular structures crafted from resin, plastic, and various organic materials, creating a striking contrast between wild mutation and geometric order. His work navigates the tension between nature’s unpredictability and human attempts to frame and contain it, inviting viewers to confront the fragile boundary between reality and fantasy.

Amblypgi spnifier, iridescent exoskeleton used for blinding prey.

Body -Red scarab beetle -Torynorrhina flammea -Malaysia Legs -Tailless whip spider -Amblypygi -Northern US Pincers -Thai black scorpion -Heterometrus spinifer -Thailand Amblypgi spnifier, iridescent exoskeleton used for blinding prey. Height: 35mm Weight: 40g Distant universe or a distant future? A minute tweak in Earth’s living conditions could cause evolutionary chaos. These specimens are indeed all made from real insects from the real planet we live on. But we imagine how they might have formed in places where the gravitational pull was 9.5 metres per second squared, not 9.8. Oxygen at 19%, not 21%, and the temperature just a few degrees higher or lower on average. Perhaps they were sent to us by an alien race, in tiny little rockets as tiny little gifts. So cute. Perhaps they were sent at us in tiny little rockets, as tiny little parasites. Death by pincer, death by poison. Maybe they are from our planet but they were sent back in time. Maybe they found their own way back. Futuristic lifeform that now rules the Earth in the year 322025. Neo-insect time travel using venom webs. Maybe they are from the pre-historic past, slowly burrowing their way through the earth’s crust over the last 250 million years. The heat preserving their bodies as they almost starve on a diet of hydrocarbons and radioactive minerals. Alfie Greenwood, born in the Forest of Dean in England, moved to Berlin at the start of 2024. His artwork explores the alchemy of taxidermy and imagination by merging parts from different insects to create mutant creatures. These hybrids balance between chaotic organic forms and mythical deviations in evolution, embodying a surreal distortion of natural life. Alfie presents these mutant insects in encased quadrangular structures crafted from resin, plastic, and various organic materials, creating a striking contrast between wild mutation and geometric order. His work navigates the tension between nature’s unpredictability and human attempts to frame and contain it, inviting viewers to confront the fragile boundary between reality and fantasy.

Neurobasis Damselsect – exoskeleton photosynthesis, wilts in the winter

Body -Leaf insect -Pulchriphyllium -Indonesia Wings -Damselfly Neurobasis Damselsect – exoskeleton photosynthesis, wilts in the winter. Height: 60mm Weight: 2.8g Distant universe or a distant future? A minute tweak in Earth’s living conditions could cause evolutionary chaos. These specimens are indeed all made from real insects from the real planet we live on. But we imagine how they might have formed in places where the gravitational pull was 9.5 metres per second squared, not 9.8. Oxygen at 19%, not 21%, and the temperature just a few degrees higher or lower on average. Perhaps they were sent to us by an alien race, in tiny little rockets as tiny little gifts. So cute. Perhaps they were sent at us in tiny little rockets, as tiny little parasites. Death by pincer, death by poison. Maybe they are from our planet but they were sent back in time. Maybe they found their own way back. Futuristic lifeform that now rules the Earth in the year 322025. Neo-insect time travel using venom webs. Maybe they are from the pre-historic past, slowly burrowing their way through the earth’s crust over the last 250 million years. The heat preserving their bodies as they almost starve on a diet of hydrocarbons and radioactive minerals. Alfie Greenwood, born in the Forest of Dean in England, moved to Berlin at the start of 2024. His artwork explores the alchemy of taxidermy and imagination by merging parts from different insects to create mutant creatures. These hybrids balance between chaotic organic forms and mythical deviations in evolution, embodying a surreal distortion of natural life. Alfie presents these mutant insects in encased quadrangular structures crafted from resin, plastic, and various organic materials, creating a striking contrast between wild mutation and geometric order. His work navigates the tension between nature’s unpredictability and human attempts to frame and contain it, inviting viewers to confront the fragile boundary between reality and fantasy.

-uzYmDg3r.jpg)

The Saltamontes 3142 – breathes pure carbon dioxide.

Red wings -Giant red winged grasshopper -Tropidacris cristata -Costa Rica Brown wings + head -Leaf insect -Pulchriphyllium The Saltamontes 3142 – breathes pure carbon dioxide. Height: 15mm Weight: 4g Distant universe or a distant future? A minute tweak in Earth’s living conditions could cause evolutionary chaos. These specimens are indeed all made from real insects from the real planet we live on. But we imagine how they might have formed in places where the gravitational pull was 9.5 metres per second squared, not 9.8. Oxygen at 19%, not 21%, and the temperature just a few degrees higher or lower on average. Perhaps they were sent to us by an alien race, in tiny little rockets as tiny little gifts. So cute. Perhaps they were sent at us in tiny little rockets, as tiny little parasites. Death by pincer, death by poison. Maybe they are from our planet but they were sent back in time. Maybe they found their own way back. Futuristic lifeform that now rules the Earth in the year 322025. Neo-insect time travel using venom webs. Maybe they are from the pre-historic past, slowly burrowing their way through the earth’s crust over the last 250 million years. The heat preserving their bodies as they almost starve on a diet of hydrocarbons and radioactive minerals. Alfie Greenwood, born in the Forest of Dean in England, moved to Berlin at the start of 2024. His artwork explores the alchemy of taxidermy and imagination by merging parts from different insects to create mutant creatures. These hybrids balance between chaotic organic forms and mythical deviations in evolution, embodying a surreal distortion of natural life. Alfie presents these mutant insects in encased quadrangular structures crafted from resin, plastic, and various organic materials, creating a striking contrast between wild mutation and geometric order. His work navigates the tension between nature’s unpredictability and human attempts to frame and contain it, inviting viewers to confront the fragile boundary between reality and fantasy.

-7h9NUeIO.jpg)

The tenoderian gliding spider mantis, passing through the altitudes of infinity

Wings: -Chinese Mantis -Tenodera Sinensis -China Tail + head: Nephila Pilipes -Giant Golden Orb Weaver Spider -Hong Kong Back striped wings -Red Devil Cicada Heuchys Incarnata -Indonesia The tenoderian gliding spider mantis, passing through the altitudes of infinity. Height: 40mm Weight: 25 grams Distant universe or a distant future? A minute tweak in Earth’s living conditions could cause evolutionary chaos. These specimens are indeed all made from real insects from the real planet we live on. But we imagine how they might have formed in places where the gravitational pull was 9.5 metres per second squared, not 9.8. Oxygen at 19%, not 21%, and the temperature just a few degrees higher or lower on average. Perhaps they were sent to us by an alien race, in tiny little rockets as tiny little gifts. So cute. Perhaps they were sent at us in tiny little rockets, as tiny little parasites. Death by pincer, death by poison. Maybe they are from our planet but they were sent back in time. Maybe they found their own way back. Futuristic lifeform that now rules the Earth in the year 322025. Neo-insect time travel using venom webs. Maybe they are from the pre-historic past, slowly burrowing their way through the earth’s crust over the last 250 million years. The heat preserving their bodies as they almost starve on a diet of hydrocarbons and radioactive minerals. Alfie Greenwood, born in the Forest of Dean in England, moved to Berlin at the start of 2024. His artwork explores the alchemy of taxidermy and imagination by merging parts from different insects to create mutant creatures. These hybrids balance between chaotic organic forms and mythical deviations in evolution, embodying a surreal distortion of natural life. Alfie presents these mutant insects in encased quadrangular structures crafted from resin, plastic, and various organic materials, creating a striking contrast between wild mutation and geometric order. His work navigates the tension between nature’s unpredictability and human attempts to frame and contain it, inviting viewers to confront the fragile boundary between reality and fantasy.

-TUSmeHzZ.jpg)

Actias Orb Luna Morpion – “fluttering pince”.

Wings -Actias luna -Luna moth -Canada Legs: -Nephila Pilipes -Giant Golden Orb Weaver Spider -Hong Kong Actias Orb Luna Morpion – “fluttering pince”. Height: 120mm Weight: 250g Distant universe or a distant future? A minute tweak in Earth’s living conditions could cause evolutionary chaos. These specimens are indeed all made from real insects from the real planet we live on. But we imagine how they might have formed in places where the gravitational pull was 9.5 metres per second squared, not 9.8. Oxygen at 19%, not 21%, and the temperature just a few degrees higher or lower on average. Perhaps they were sent to us by an alien race, in tiny little rockets as tiny little gifts. So cute. Perhaps they were sent at us in tiny little rockets, as tiny little parasites. Death by pincer, death by poison. Maybe they are from our planet but they were sent back in time. Maybe they found their own way back. Futuristic lifeform that now rules the Earth in the year 322025. Neo-insect time travel using venom webs. Maybe they are from the pre-historic past, slowly burrowing their way through the earth’s crust over the last 250 million years. The heat preserving their bodies as they almost starve on a diet of hydrocarbons and radioactive minerals. Alfie Greenwood, born in the Forest of Dean in England, moved to Berlin at the start of 2024. His artwork explores the alchemy of taxidermy and imagination by merging parts from different insects to create mutant creatures. These hybrids balance between chaotic organic forms and mythical deviations in evolution, embodying a surreal distortion of natural life. Alfie presents these mutant insects in encased quadrangular structures crafted from resin, plastic, and various organic materials, creating a striking contrast between wild mutation and geometric order. His work navigates the tension between nature’s unpredictability and human attempts to frame and contain it, inviting viewers to confront the fragile boundary between reality and fantasy.

-txzRufZk.jpg)

No Game Over

No Game Over is a stop-motion animation that brings to life the modular fungal composite blocks cultivated during the MycoHackers workshop series at TopLab Berlin, led by Alessandro Volpato. The project draws from a collaborative process involving students, artists, and researchers who co-designed and grew Tetris-like pieces from mycelium-based materials. Inspired by the classic logic of gameplay, MYCO-TETRIS transforms a digital metaphor into a living, decomposing system. Each block, once placed, begins to vanish—mirroring the natural cycle of fungal materials that decompose within thirty days. The animation invites reflection on circular design, impermanence, and co-creation with living matter, celebrating the MycoHackers ethos of playful, sustainable, and multispecies collaboration. By reimagining a game about permanence and accumulation into one of ephemerality and decay, MYCO-TETRIS suggests a new kind of ecological play—where disappearance is not loss but renewal.

MYCO-TETRIS

About the Project MycoTetris was a collaborative experiment exploring the intersection of play, mycofabrication, and community learning. Conceived as a fungal game of construction, it invited participants to design and grow modular Tetris-like blocks using mycelium cultivated on agricultural residues such as hemp. The project introduced participants to co-designing with living organisms, using the familiar logic of Tetris to make fungal growth and material learning accessible and engaging. Under the guidance of Alessandro Volpato, participants produced numerous mycelium blocks through a simplified and playful fabrication process. The activity transformed biofabrication into a collective and educational practice that bridged sustainability, design, and biology. Background: MycoHackers MycoHackers originated in 2023 within the TopLab community as a grassroots initiative connecting fungi, bioart, and citizen science. It was shaped through the collaboration of Melissa Ingaruca, Alessandro Volpato, and Xristina Sarli. Melissa Ingaruca contributed to the early conceptualization of MycoHackers and co-led workshops on bioluminescent fungi through her Endarken project at TopLab and Floating University. Alessandro Volpato guided the mycofabrication aspects of the collective, building upon the legacy of Mind the Fungi – Engage with Fungi and transforming it into a hands-on, community-oriented practice. Xristina Sarli curated and co-organised the events that initiated MycoHackers as an open community under TopLab’s infrastructure. They linked the projects to broader art–science–technology platforms and diverse audiences, managed social media and public communication, and shaped the visual identity of the collective by creating logos, visuals, and digital content. Sarli also co-hosted workshops, contributed to documentation, and art-directed the digitalisation of tutorials and formats that extended the project’s reach into online and XR contexts. Production and Collaboration The MycoTetris blocks presented here were produced by Alessandro Volpato and participants during courses, workshops, and training sessions held at Bauhaus University Weimar, HTW Berlin, Kunstverein Wolfsburg, MycoHackers, SYLIA Project, and TU Berlin. Each mycelium block was grown separately and later assembled — allowing the living material to fuse together, demonstrating its capacity to regenerate and connect across boundaries. This process mirrored the philosophy of modular learning and co-creation central to the MycoHackers approach: a distributed, open-source way of making with life. Legacy and Continuation While MycoTetris originated as part of the MycoHackers activities, it continues as an ongoing project by Alessandro Volpato, expanding into new educational and research contexts. The iteration presented in The Wrong Biennale 2025 revisits the collaborative phase between Alessandro and Xristina, highlighting the collective energy and shared knowledge that shaped its early development. Through this documentation — including 3D scans, workshop traces, and digital archives — MycoTetris remains a living record of how community learning, fungal intelligence, and playful experimentation can merge into a sustainable design practice.

MYCO-TETRIS